Jonathan Cowie

(August 2009)

Since my two climate books came out (1998 and the 2007 one that currently seems to be garnering rather kind reviews) I am constantly asked a number of similar climate science questions. These handful of key posers relate to where we and our biosphere are going. With hindsight both books seem to have had their predictive elements and so years on I feel somewhat emboldened to present some answers in writing. Indeed, as I have recently (summer 2009) been asked to speak next year at a number of meetings on topics that very much relate to these questions, I thought it helpful (if nothing else for purposes of my own preparation) to jot down a few thoughts to mark the release this year (2009) of my 2007 book's electronic edition by Cambridge U. Press. These are they…

(For latest news see article's end.)

The question I am most asked by members of the public remains as to whether climate change, in the form of human-induced global warming, is taking place? That there is such doubt as to the reality of global warming may come as a surprise to many scientists but actually professional surveys as recent as 2007 (for example reference '1') show that about half the UK public still thinks that the science jury is still out as far as the threat of serious global warming is concerned! Anecdotally I can confirm this, both amongst the public and also (more surprisingly) some UK politicians: I presume this is also true of some (many?) other groups of people. I do not want to dwell on this now as I have covered this as part of another book I recently completed and which is currently under submission to publisher agents. Yet I mention it as this really is one of the questions I am often asked.

Conversely (non-climate) scientists – biologists, ecologists, geologists and others some of whose work is driven by global warming concerns – ask a suite of questions that are best summed up as to 'whether or not we will properly manage the threat of serious global warming?' The suite of questions themselves often have inherent assumptions so after I have had half an hour's conversation with some folk you actually get to the real questions they would have asked had they not accepted much of the climate baggage found in the popular media. These post-2007-IPCC, core climate questions can be summarised as:-

- Is the presumed degree of the warming threat really that serious?

- What levels of warming and of carbon dioxide are safe?

- Can we avoid this threat of serious warming (and carbon dioxide limit)?

- What happens if we do not try to avoid this threat?

- Is there anything else of which we should be aware? (Is there any other bad news?)

- Is there any good news?

Now this first question most people – who have read around the subject and who have at least school-level science – can answer the easiest. The second one – on warming avoidance – is one that climate scientists tend to duck as energy policy matters are not covered by their discipline, but it is by those of us into human ecology and energy resource use. The third question, of failing to try to avoid the climate threat, actually turns out to have a barb to it which I covered back in my 1998 climate book Disaster or Opportunity? (2), indeed Lord Nicholas Stern more than touched upon it in his 2006 The Economics of Climate Change (3) report: though others are slowly coming round. Meanwhile the what-happens-if-we avoid-tackling greenhouse concerns question is still (surprisingly) ignored by the media and politicians: I suspect because they think the answer is obvious. Then there are the questions of the possibility of there being further bad news and good news lurking in the science and human ecology underpinning the climate debate. Here the answer to both is 'yes' but they have been very much buried in the IPCC small print and are not out front in climate discussions as (I feel) they should.

Of course at this stage I should point out that my views are neither maverick, illogical (but then I would say that), nor unique to a small cadre of experts far out on left field: instead they are drawn upon established centre-field science. So I back this article up with a handful of references to respected publications and papers from respected journals (see this article's end). In short, while my views may not (yet) be mainstream (in the IPCC sense), my perspective has been, and is, echoed by more than a few other scientists: so consider the references at this article's end corroboration should you require it in the event you feel a logical argument alone is unsustainable.

Before I continue, so as to prevent this article from being overly long, I will assume that the IPCC views are sound; that is to say sound as far as they go. I take it that fellow scientists active in climate science, biosphere (Earth systems) science and the human ecology of energy use will accept this assumption. (If not then go argue with the IPCC, not me.)

Now on to the questions…

Is the presumed degree of the warming threat really that serious?

It does really depend on what 'you' mean by serious?

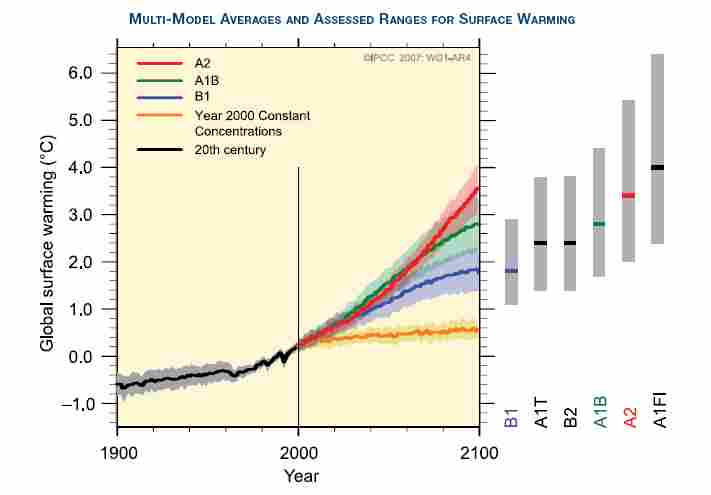

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's 2007 scientific assessment (4) gives a range of 1.1 - 6.4ºC anticipated warming for the key high-low boundaries for the IPCC's standard scenarios from the Earth's 1990 (actually a 1980-1999 average) temperature through to the end of the twenty-first century. (This includes the least likely warming if we try to curb emissions, through to a greater warming that might reasonably be expected if we carry on with our existing (growing) burning fossil fuel trends.) To cut a long story short (for there are many IPCC scenarios), the mid-range scenarios tend to forecast warming roughly between 2 - 4 ºC from 1990 to 2100 (1990 being the base year used by the Kyoto Protocol). See also the graph below of these IPCC scenario forecasts from 2000 -2100.

IPCC 2007 warming forecasts. (Copyright: IPCC. This figure is reproduced here under the IPCC's blanket, unaltered, non-commercial use, citing-source permission, namely: page 14 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) Climate Change 2007: the Physical Science Basis - Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.)

The black line to 2000 is the actual global temperature. The zero on the temperature axis is the 1980-1999 average (which roughly approximates to the temperature around the year 1990, the year of the first IPCC report and a key reference date for Kyoto Protocol purposes.) The blue green and red lines are forecasts should we follow three different core IPCC greenhouse gas emission scenarios. The bottom orange line is a hypothetical case for warming if we stopped releasing nearly all the carbon dioxide into the atmosphere so as to hold atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases constant at 2000 levels. (Here the very slight rise after 2000 despite atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations remaining constant is due to the Earth slowly adjusting to a slightly warmer stable temperature.)

To put this 2 - 4 ºC warming window for the 21st century into context, the average global temperature was about 5 ºC or so cooler than 1990 during the depth of the last ice age (glacial). In short we will, over the next hundred years give or take a decade or two, warm the Earth by the same temperature difference as between now and the depth of the last ice age (glacial) some 25 thousand years ago!

The important thing to note that the IPCC forecast window to the year 2100 is purely arbitrary even though you hear a lot about it in the media: there is no particular reason why the IPCC stopped their forecast at that particular date. In 2100 warming does not suddenly, miraculously halt: in fact the opposite happens, it actually continues! So our current pulse of warming – that comes from burning economically recoverable fossil fuel reserves (and deforestation) – is not somehow confined to a single-century forecast window. In reality the global temperature stabilises a few centuries from now, a little after the IPCC scenarios predict we stop emitting greenhouse gases (presumably because economic fossil fuel reserves run out).

You can see from the above IPCC's summary warming graph that all but one of their scenarios – the one for the least dependent on fossil fuels – as well as their hypothetical, constant-greenhouse-gas scenario (albeit only very slightly), show the Earth being on a clearly upward warming trend in the 21st century, and so presumably also after it ends. In short the world of the IPCC forecasts will certainly become even warmer after 2100!

Bearing in mind that the depth of the ice age (glacial) saw the Earth about 5ºC cooler than 1990, and the radical alteration in the Earth's biomes, and their ecosystems since then compared to now, and you can make your own mind up as to whether or not warming in excess of 2 - 4 ºC by the end of the 21st century is serious? You also might like to think about the 22nd century world your great great grand children will inherit.

What levels of warming and of carbon dioxide are safe?

Warming limit

Dealing with the warming first: the upper limit – that is to say the maximum – for my safe zone as to how much warming our world's natural systems can take without coming to undue harm, being a bioscientist, I consider this to be the greatest temperature at which the Earth has seen for the past few million years of hominid (human and early human) life in which our species has thrived. This takes us back to the mid-Pliocene some three million years ago. It was a time when early hominids were evolving. It was also a time by which the Antarctic ice sheet was clearly established. This time therefore is one of our (modern human) species' evolutionary roots and, as important, it is also the time at which a good number of the most recent cadre of species upon which we rely evolved (especially the larger animals). The Earth's temperature at this time was getting on for 2 - 2.5ºC warmer than it was around 1990: or up to around 3.0ºC above the pre-industrial (18th century) temperature. Even so, that Earth was a markedly different place back then than today and the early hominids back then did not have the sentience of much later human species such as Homo neanderthalensis and H. sapiens sapiens.

Now, if getting on for 2.5ºC warmer than the late 1990s (around 3.0ºC pre-industrial) is the 'upper' limit of safe warming, what might a reasonable limit be? Well over the past two million years (the Quaternary) the Earth has seen a series of very cold times called glacials (colloquially known as 'ice ages), with each of these being roughly 100,000 years long and interspersed with short (a few or more thousand years) warmer times called interglacials such as the one we are in now (and have been in for the past ten thousand years). Over the past quarter of a million years the warmest these warm interglacial periods have been is about 2ºC warmer than pre-industrial times (or about 1.6ºC warmer than 1990 or 1.2ºC warmer than the Earth was in 2006/7).

It is important to note that as a species we have only had civilization during roughly the latter half of our current 10,000-year interglacial. (As someone into biological science communication I define 'civilization' as the time since we have had coherent writing and domesticated crop plants.) Here the warmest the globe the past 10,000 years has been a fraction of a degree or so warmer than the late 1990s (possibly 0.1 or 0.2ºC warmer) or roughly 0.7ºC above pre-industrial times, and the average global temperature was only this warm for a few centuries, if that, at a time.

Of note we must remember that global average temperatures are one thing, but that regional (especially near the poles) temperature changes can be greater than the global average. So just as on any day parts of the Earth are warmer than the global average and other parts cooler, so with climate change over the years parts experience greater warming and other parts less. Indeed temperatures around the poles seem to vary more than those in the tropics and indeed we are seeing this now with present-day warming. So even if we opt for what some may consider a low warming limit of a couple of a degrees, parts of the Earth would still see greater warming than this!

For all these reasons the arguably safe-warming limit, it would be most prudent to try to avoid exceeding, might be about 2ºC above pre-industrial level (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature), and as it happens this is the warming limit that some policy makers (such as the European Union) are taking as the safe limit.

It should be noted that this geologically historic temperature argument is not the sole reason for keeping below this limit. Because the Earth has been cooler than this for hundreds of thousands of years it is very likely that carbon has accumulated in parts of the biosphere over this time. It is therefore all too possible that should the Earth warm above this limit this carbon would be released from these biosphere reservoirs into the atmosphere in much the same way that methane (another greenhouse gas) is currently being released from some boreal regions that were until recently firmly areas of permafrost. (See also the section below 'Is there anything else of which we should be aware?'.) This extra carbon would add to our current human-induced greenhouse warming and so be a form of positive feedback propelling us into an even warmer world.

In short, this 2ºC above pre-industrial value is not some arbitrarily chosen warming limit: it is based on clear evidence-based reasoning.

Even so it would probably best not to call this a safe limit but a 'comparatively safe' limit. It is a bit like drinking and driving: what is the safe alcohol limit? That different countries have different limits is testimony to there being no hard-and-fast level we can say is truly safe. Similarly how much warming is truly 'safe' is not hard-and-fast. This is especially true because we now live in a crowded world. Conversely, if we lived in a sparsely populated world then we could easily move away from spreading deserts or worry less if snow-melt fed rivers were dry in summers. Also there would be plenty of room for wildlife reserves. So if we lived in a sparsely populated world we could tolerate greater global warming without our food supply being compromised or great biodiversity loss: there would be plenty of room for both human-managed and natural ecosystems. This, though, is wishful thinking as we do live in a crowded world: indeed it is becoming more crowded year-on-year. (We will return to global population shortly when looking at the question of Can we avoid the threat of serious warming (and carbon dioxide limit)?)

Carbon dioxide limit

Currently (2009) the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide is around 388 parts per million (ppm).

This compares to a late 18th century (pre-industrial) concentration of around 280 ppm.

So what limit would atmospheric carbon dioxide have to be kept to avoid warming the planet by our hypothetical safe limit of 2ºC?

Now this is more complex a question than it seems because carbon dioxide is not the only greenhouse gas. Nonetheless carbon dioxide alone does account for about half of all human-induced greenhouse warming: it is the most important greenhouse gas and the one with which most people (including policy makers) can identify, and so it is worth having a stab at looking at what might be a safe carbon dioxide limit.

Carbon dioxide (notably along with methane) has fluctuated very closely with global temperature through successive glacials and interglacials. Antarctic ice cores (which contain bubbles of air trapped when the snow originally fell) show that before the industrial revolution (18th century), and for the previous 650,000 years atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, were always between 180 and 300 ppm.

Yet our current (2009) carbon dioxide level is 388 ppm, but we are only about 0.8ºC above the pre-industrial global average (0.3ºC warmer than 1990). In short we have about another 1.2C to go before we reach our 2ºC above pre-industrial, 'comparatively safe' warming limit. This suggests that, as we have a little temperature lea way, we might safely allow carbon dioxide to rise a little above its current level. Indeed carbon dioxide is still rising year-on-year so it looks as if we do not have much choice in the matter but to see additional greenhouse-induced warming (let alone the future warming already inherent in our world's system).

Given all this, and indeed (dare I say it) a superficial reading of the latest IPCC 2007 scientific assessment report (4), can lead one to the notion that we might allow carbon dioxide to rise a little way and yet stay within our 2ºC 'comparatively safe' warming limit. For this reason (among others) the figure of 450 ppm has occasionally been cited as a safe limit for carbon dioxide concentration: it is after all a nice round number that is neither too far off current levels yet not so close as to seem an unreasonably constraining; in other words the number '450' has psychological appeal.

This 450 ppm limit is not that hard to present as a target especially as most politicians are not scientists and so only really get to grips with the IPCC's report's 15-page summary for policy makers. True, some politician might venture into the 70-page technical summary but how much of even this will the average (albeit climate interested) member of Parliament (or Congress) really understand? In fact the whole IPCC's 2007 scientific assessment report(4) is just a few pages short of a thousand (and additionally there are two other accompanying volumes), and I would be very surprised indeed if more than one or two (if any) of Britain's six hundred or so members of Parliament have read it all; indeed, I am fairly certain that even if any have, that none have the climate and biosphere scientific background to read between the lines. Yet read between the lines you must if you are to get to grips with the thorny question of what is a safe carbon dioxide limit. Here chapter 10 of the IPCC's scientific assessment(4) is key and in a box on page 826 we see that with 450 ppm the Earth would have a 'best guess' stable temperature some 2.1ºC above pre-industrial levels. This too is in line with the perception that we might allow carbon dioxide concentrations to rise a little further and yet stay if not within the 2ºC warming limit not much over it.

Yet is this an accurate representation of what the IPCC is saying? Well it is certainly a reflection of what the IPCC is saying, but the devil is in the IPCC detail.

You see the IPCC notion that with 450 ppm the Earth would have a stable temperature some 2.1ºC above pre-industrial levels is just that: a notion. More specifically it is a 'guess'. A 'best guess' yes (which is exactly what the IPCC call it), but a guess nonetheless for it is based on computer models of the global climate system. Here, though I appreciate computer models as a very rough guide as to possibilities, I am all too aware of their limitations (see pages 216, 233, 254, 453, and 463 of reference '5') and I prefer instead to look at the Earth's past climate regimes as a guide to the future where it has been both warmer and cooler than today. This is why I devoted over 160 pages of my 500-page 2007 book(5) to past climates and their determination. This is just as valid approach as the IPCC's computer model one and indeed – forgive me for being repetitious – where the IPCC do refer to 450ppm making the Earth 2.1ºC warmer they themselves refer to it as a 'best guess' (page 826 reference '4').

This detail is important for the IPCC also say that at 450 ppm the Earth's stable temperature is likely to be in the range straddling its 'best guess' of 1.4 - 3.1ºC warmer than pre-industrial temperature (with 2.1ºC in the middle); of course if it ends up being the latter (3.1ºC) then our 'comparatively safe' 2ºC warming would have exceeded.

So to be safe, and using the IPCC's figures for carbon dioxide concentration to end up with a 'best guess' long-term equilibrium temperature below 2ºC warming (but with a 'likely-in-the-range' error margin taking us up to 2ºC) then their figures (see page 826 reference '4') suggest atmospheric carbon dioxide should be kept to about 400 ppm. Indeed allowing this error margin would be wise as the IPCC here refer to equivalent carbon dioxide concentration that includes other greenhouse gases such as methane and so the absolute carbon dioxide concentration would indeed be lower than they cite. The IPCC also have a hefty caveat paragraph warning that, notwithstanding their estimate, there are likely to be unforeseen factors.

In short even 400 ppm might be too high!

Then, for completist sake, there is the question of whether carbon dioxide levels might be too low. The late 18th century concentration of 280 ppm is itself at the upper end of a consistent carbon dioxide concentration window of 265-280 ppm from around 10,000 years ago (after the end of the last ice age (glacial)) until the onset of the industrial revolution. (Indeed greenhouse effect of the fluctuations within this window have in part been offset by changes in methane concentration over this time.) Yet this 10,000-year window gave us climate periods such as the Little Ice Age, and so arguably a good target concentration would be higher than 280 ppm.

To summarise, my view is that a safe level of carbon dioxide concentration could still be above 280 ppm but below 400ppm.

Beyond this I cannot say, such is my limited ability to interpret the science within the academic literature. Others have come up with a more precise figure within this window. Of note James Hansen suggests 350ppm (6) as this was the concentration a few million years ago at which point a significant Antarctic ice cap began to be formed: the implication being that above this level the Earth might see the Antarctica melt. Here I should point out that there are contrary arguments in that a world with a large Antarctica ice sheet (as we currently have) sees more energy reflected away from its ice-white surface than a world without (or yet to have) one (as there was over 20 million years ago) and so the bulk of our present Antarctic ice sheet could well be stable at 350 ppm. Yet again 'could' is not the same as 'would'.

The bottom line is that irrespective of whether or not you accept my 'safe' limit of 400 ppm or Hansen's 350ppm, considering we are currently (2009) at 388ppm, means that in a few years time – by somewhere around 2015 give or take a year or so – we are going to reach 400 ppm be it safe or not!

Can we avoid this threat of serious warming (and carbon dioxide limit)?

Keeping global warming below 2ºC above pre-industrial levels (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature) and keeping carbon dioxide concentrations below 400ppm is going to be extremely difficult due to two fundamental reasons. 1) We are each and every one of us on the planet, rich or poor, on average individually consumes more energy a year than before. This individual growing energy consumption trend has been continuing for a couple of centuries. 2) The human population is also increasing: it was less than 2 billion at the start of the 20th century and over 6 billion by its end! By the middle of the 21st century the UN estimate that it could be getting on for around 9 billion. In 2007 (5) I concluded:

Since 2007 there has been nothing new to change my opinion. Indeed today I would go further and say that we are most likely to have significant warming that will take us above the comparatively safe 2ºC limit. Certainly fossil fuel energy trends (chapter 7 section 7.2 of ref '5') are still going in the wrong direction almost two decades after the first IPCC report in 1990 (7). Furthermore, given both the growing global population and per capita energy consumption hence the size of the energy gap to be filled by the middle of our century, it seems difficult to see how we can meet energy demands without consuming fossil fuel at an even faster rate than now in the next few decades (chapter 8 section 8.4.1 of ref '5').

Alas my pessimism is also reflected by others. Interestingly (from a science perspective) the way I came to my conclusion and the way some others have come to theirs differs. Indeed, that there are a number of different approaches to this problem that all come to the same broad conclusion does (I venture) suggest that this conclusion has some merit.

I first presented my very simple – but, I contend, illustrative – approach as to our likely ability to reduce carbon dioxide emissions in 1998(2) and then again in 2007(7). (An environmental scientist should recycle resources.)

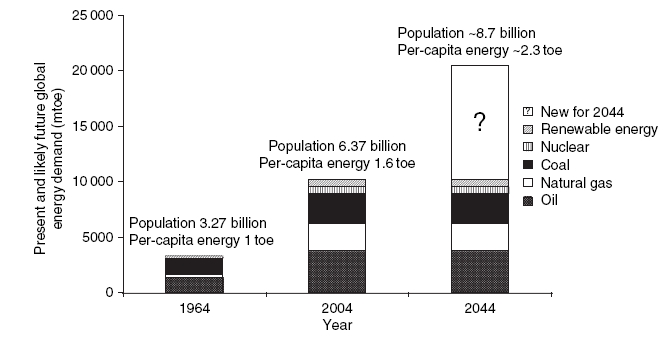

Simply, what I did was to look at how much energy in its different forms (both fossil carbon and non-fossil) we as a species have used each year over the 20th century. Next I looked at global population (fortunately the United Nations attempts to keep track of this) as well as its likely growth in the 21st century (the UN forecasts this too). It was then possible to see how much energy each individual consumes through the 20th and is likely to consume in the first half of the 20th century. Given this it was possible to estimate what global energy demand might be like for the middle of the 21st century given the mid-UN population growth estimates and the global per capita energy consumption trend through the 20th century to 2004. Note: here I assumed that the rate of growth in energy consumption per person would decline in the 21st century and also accepted the UN forecast that population growth would be less. In 2007 (7) so as to illustrate the global energy challenge I looked at the 40-year period between 1964 and 2004 and then the 40-year period between 2004 up to 2044.

Now, I accept that this is a very rough-and-ready forecast but it does give us a handle on the rough size of our likely mid-21st century energy problem: will it be big or will it be small etc? Also I must repeat I was not being alarmist: I accepted the UN's population forecast that 21st century population growth would be markedly less than 20th, and I assumed (looking at industrialised/developed nation energy consumption patterns) that – as the 21st century would be more developed and industrialised – growth in individual energy consumption would be less than in the 20th century. I could then present the results as a bar graph of past, present and possible mid-21st century (2044) global energy consumption in million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe). It was also possible to note by each bar the past actual and mid-UN forecast of global population, as well as how much energy each person on the Earth consumed in tonnes of oil equivalent (toe). Finally, to proved a base for comparison, the energy breakdown how energy was produced to meet demand in 1964 and 2004 was given; though how we would meet the likely energy gap in 2044 could only be denoted by a question mark. This question mark was the estimate as to the rough size of our global energy problem.

The result (see the graph below) was that the estimated global energy demand would broadly double in the 40-year period from 2004 to 2044 compared to the 40-year period up to 2004.

This begs the question where would this extra energy come from? This is a fundamental question given that in 2004 we relied on fossil fuels to meet over 87.6% of our global energy demand and assuming that fossil fuels would probably meet at least part of the probable energy gap in 2044, then the likelihood (if not certainty) is that early 21st century fossil fuel demand is likely to go up and not down! This then is the probability, of course it is possible that we will have a very radical shift in the way the World meets its energy demand: but this is exactly the point, what is required is a very radical shift.

Source: Cowie, J., (2007) Climate Change: Biological and Human Aspects. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Given that even back with its first report (7) the IPCC said that if we were to stabilise carbon dioxide at the then (1990) present day levels it would require an immediate reduction of about 60-80% of carbon dioxide emissions, facing an almost certain early 21st century increase in fossil fuel use does suggest the equally almost certain prospect of further warming! Even if the size of this energy gap was only half of that forecast above, it is difficult to see how this extra energy demand will be met without using additional fossil fuel even if both nuclear and all renewable energy increased many fold! What we are not on track to do is to reduce fossil fuel consumption, hence emissions, by 60-80% as per the IPCC.

Now, while this sinks in, you may care to note the detail in the above statement. I said given current trends we are on track to more than double our energy use. Yet the above figure does not present current trends in a linear (straight-line) way. Note – and forgive me for repeating this yet again – that population between 1964 and 2004 increases by 94% and yet between 2004 and 2044 I have only had it rising to 8.7 billion and increase of just 37%: in short estimated population growth greatly slows over the next 40 years from 2004 compared to the previous 40 years. Again as I have said this is in line with UN forecasts. Also note that per capita energy production increases from 1 toe (tonnes of oil equivalent) to 1.6 an increase of 60% but between 2004 and 2044 it is only forecast to increase to 2.3 toe, an increase of just 44%. In short the rate of individual increase in forecast energy consumption also slows markedly from its historic pattern of the past four decades. Add this two reducing effects together and the forecast global energy demand of over 20,000 mtoe for 2044 is significantly less than the 22,300 mtoe if late 20th century growth patterns had continued as they had previously.

What this all suggests is that even to restrict the World energy demand to simply double over the four decades to 2044 will need a marked change of trends (both a reduction in population growth and a reduction in individual growth of energy demand). We are therefore very far from stabilising fossil demand let alone actually reducing carbon emissions.

All in all this rather suggests that we can expect warming to continue and for it to continue above our 'safe' 2ºC above pre-industrial level (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature).

So what of the notional safe carbon dioxide limit of 400 ppm. Well, I answered that at the end of the previous section, given that in 2009 carbon dioxide was 388ppm, you can draw your own conclusions.

The above is my take on the problem. Others have approached matters differently, but if you tease apart the numbers and it can be seen that they come to the same conclusion.

For example, more recently, in April 2009, Malte Meinshausen and his European team published a paper(8) in the journal Nature suggesting there was only a 50% probability or less that we might keep within the 2ºC above pre-industrial temperature if we kept emissions in the first half of the 21st century to 1,440 Gt CO2 (or 393 Gt carbon). However the paper notes that between 2000 – 2006 total emissions were about 234 Gt CO2 (or 64 Gt C). Given this they assume that the World leader (G8) goal of halving emissions by the middle of the century might just keep us within the 2ºC but only with less than 45% probability! This last is a very difficult target to meet and so represents a big assumption that it is achievable. Given what the Meinshausen team have said is required, you can only make your own mind up as to whether or not we can hope to realistically achieve it?

As it happened the afore paper(8) was twinned with another(9) in the same 2009 issue of Nature (indeed some of the authors were the same). This showed that as far as the 21st century was concerned it was not so much the annual level of carbon emissions that was important in determining the warming that would result but the total amount of carbon dioxide emitted historically effectively since the inductrial revolution. It concluded that we had to avoid putting a trillion tonnes of carbon (C) into the atmosphere (or 3.67 trillion tonnes CO2) in order to stand a good chance of keeping within our 'safe' 2ºC above pre-industrial level (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature).

To do this we would need to keep our emissions rate no higher than 2000 – 2006. The problem here is that over the period 2000-2006 fossil fuel emissions were themselves rising and had increased by 20.5%, and growth has continued since then. Furthermore, what happens after the end of the 21st century?

There is also another problem. The Meinshausen Nature paper(8) confines itself to the first half of the 21st century. Yet the second paper(9) with which it was published concludes that it is the total emissions past and future that count. In short with this view all lowering the rate of emission levels (unless they are very drastic) does is push the date we reach the 'safe' warming limit further into the future: it does not keep us forever within this limit, nor confine our leaving the safe warming zone to the first half of the 21st century.

To sum up. Looking at the problem in a variety of different ways still leads us to the broadly same conclusion that we must very markedly shift from our current pattern of fossil fuel use to one of far less consumption. Yet at the same time, despite the policy and political rhetoric since 1990 (the first IPCC report (7)) we have been moving in the other direction towards increased fossil fuel use and carbon emissions. So far to date (summer 2009) all we have been doing is tinkering with the problem.

Given the above, it seems very likely (without a really major change in global human behaviour) that we will exceed our 'safe' 2ºC above pre-industrial level (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature) warming. Therefore, it might seem that there is little point in trying to avoid the threats of such warming. This then is the next question to address...

What happens if we do not try to avoid this threat?

At this point in the proceedings you might expect tales of hurricanes, drought, super-heatwaves from the warmth and abnormal downpours from increased ocean evaporation and atmosphere water-carrying capacity, together with a plethora of climate related problems. Well I have outlined the way climate affects biological and human systems in Climate Change: Biological and Human Aspects(5) but there is more…

As noted earlier, the IPCC's 2007 scientific assessment is nearly a thousand large-format pages long. Few have actually read it all. However if you do you will find that the IPCC warns us to be wary of climate surprises. The climate system may not respond so smoothly as it warms and it is possible that it might jump either globally or regionally to a new state that is markedly different to what has been experienced historically. Such an occurence is a 'threshold' event.

If, as I contend, that it is too late to avoid significant climate change and that we are very likely going to exceed the our 'safe' 2ºC above pre-industrial level (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature) warming, it might seem pointless in adopting expensive low-fossil carbon economies. However the more the Earth warms the more the chance of one of these threshold events taking place.

Second, even if climate change is unavoidable, the slower it happens gives us more time to adapt and also more time to develop alternative energy resources.

Third, irrespective of climate change arguments, and the impacts on biological and human systems I outlined in Climate Change: Biological and Human Aspects(5), there is the energy argument. We really do need to wean ourselves off of cheap fossil fuels and adopt low-fossil carbon economies because – as I argued in Climate and Human Change: Disaster or Opportunity? (2) – we are fast running out of cheap fossil fuel. We are failing to find significant new reserves of gas or oil and of what we do know exists, the easy (hence cheap) to access reserves will only last a few decades: we need to switch to alternatives to cheap fossil fuel or else the lights will go out!

Taking all this together, the worrying bottom line is that at the moment globally we are using more fossil fuel than ever before. And on top of this, as mentioned before, population is growing and set to grow through to the middle of the 21st century. In short we are firmly going in the wrong direction.

So what should we do? Well, first we need to accept that we are heading for significant climate change. Exactly how great, or rather how fast, this change will be does depend on curbing greenhouse emissions. Second, we must all recognise that adapting to climate change is going to cost money. Third, to ensure we have a thriving global economy that can pay for adapting to climate change, we need to wean ourselves off finite (hence increasingly expensive) fossil fuels irrespective of (and in addition to) greenhouse motives. Those countries that do not curb carbon emissions and continue to increasingly rely on fossil fuel only serve to make it worse for us all; in any case such countries will at a later stage (when World energy is more expensive) have to either switch to alternatives or go under. In short, nobody benefits from continuing to use cheap fossil fuels other than politicians with their short-term election perspectives: even those of the public with short-term perspectives will be affected in the medium-to-longer term.

The time for indecision has now passed. Copehagen December 2009 please note!

Is there anything else of which we should be aware? (Is there any other bad news?)

Yes, there are these aforementioned threshold events. For example, one of these might be the warming of the oceans releasing methane from methane hydrates. Methane is a greenhouse gas that over a few decades is far more powerful than carbon dioxide. Another is that permafrosts, or peat lands, might be more sensitive to carbon dioxide release with warming than is thought. (For example some recent research(10) suggests that warming of just 1°C could result in northern, high-latitude peats losing 38 – 100 megatonnes of carbon a year (which is worth about 2.4- 6.3 billion Euros based on current carbon trading prices.)) Another could be that some tropical rain forests could be on the point of collapse with trees dying and in turn releasing their carbon into the atmosphere. Another might be that some ice fields (be they in west Antarctica or Greenland) might start melting a lot faster with only a little warming… You get the idea.

Is there any good news?

Now please do not take all of the afore as doom and gloom. First off, the biosphere will survive. Whatever happens life will continue on planet Earth. Secondly, we do know what we need to do and we do have the technology (or know how to develop the necessary technology) to live fully housed, fully fed and fully entertained lives with minimal land-based biodiversity loss. (Marine biodiversity will be affected by ocean acidification as it was back in the early Eocene with its pulse of carbon dioxide.) The one question I cannot answer is whether or not there is both the sufficient individual will, as well as the global leadership (we need both), for us to get there?

This last question is one to which you will have to contribute your own answer.

References

1) Downing, P., & Ballantyne, J., (2007) Tipping Point or Turning Point? Social Marketing and Climate Change. MORI Social Research Unit, London.

2) Cowie, J., (1998) Climate and Human Change: Disaster or Opportunity? London, Parthenon.

3) Stern Review (2006) The Economics of Climate Change. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

4) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) Climate Change 2007: the Physical Science Basis - Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

5) Cowie, J., (2007) Climate Change: Biological and Human Aspects. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

6) Hansen, J., Sato, M., Kharecha P., Beerling, D., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pagani, M., Raymo M., Royer D. L., & Zachos, J. C., (2008) Target Atmospheric CO2: Where Should Humanity Aim? Open Atmosphere Science Journal 2, 217- 231.

7) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1990) Climate Change: the IPCC Scientific Assessment. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

8) Meinshausen, M., Meinshausen, N., Hare, W., Raper, S. C. B., Frieler, K., Knutti, R., Frame, D. J., & Allen, M. R., (2009) Greenhouse-gas emission targets for limiting global warming to 2ºC, Nature 458, 1158-1162.

9) Allen, M. R., David J. Frame, D. J., Huntingford, C., Jones, C. D., Lowe, J. A., Meinshausen M., & Meinshausen, N., (2009) Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne, Nature 458, 1163-1166.

10) Dorrepaal, E., Toet, S., van Logtestijn, R. S. P., Swart, E., van de Weg, M. J., Callaghan, T. V., & Aerts, R., (2009) Carbon respiration from subsurface peat accelerated by climate warming in the subarctic. Nature 460, 616-619.

Stop Press Latest news! Since the above science appraisal article was written (August 2009) analyses have appeared in 2010 onwards from some reputable sources that come to the same broad conclusion as the article above that we are unlikely to keep global warming to within 2ºC! Also there has been comment by those involved in science policy at a higher paygrade than myself. These include:-

- United Nations Environment Programme (2010) How Close Are We To The Two Degree Limit? Information note to the UNEP Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum.

- Levin, L. & Bradley, R. (2010) Comparability of Annex 1 Emission Reduction Pledges. World Resources Institute, Washington. (See www.wri.org for on-line version.)

- Rogelj, J. & Meinshausen, M. et al (2010) Copenhagen Accord pledges are paltry. Nature 464, 1126-1128. This report was covered by the BBC News website on 21st April 2010.

- Friedlingstein, P., Solomon, S., Plattner, G-K. et al (2011) Long-term climate implications of twenty-first century options for carbon dioxide emission mitigation. Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/nclimate1302. Published online 20th November 2011.

- Rowlands, D. J., Frame, D. J., Ackerly, D. et al (2012) Broad range of 2050 warming from an observationally constrained large climate model ensemble. Nature Geoscience doi:10.1038/ngeo1430. Published online 25th March 2012.

- Sir Robert Watson (former Chair IPCC and Chief Science Advisor DEFRA) "Science adviser warns climate target 'out the window' -- BBC News" -- August 2012.

- Sir Nicholas Stern in an Observer article (2013) says "the risks [are] of a four- or five-degree rise."

- A Nature editorial opines that safe climate stabilisation is not realistic and that we need to prepare for some adaptation. "In 2007, some scientists

and many environmentalists were still loath to talk about adapting to climate change. The policy focus was squarely on reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, and even talking about adaptation was often seen as defeatist. Thankfully, that sentiment has faded..."

Nature (2014) 'Brace for impacts', vol. 508, p7.

- A Nature comment calls to ditch the 2ºC warming limit goal. "Politically and scientifically, the 2°C goal is wrong-headed. Politically, it has allowed some governments to pretend that they are taking serious action to mitigate global warming, when in reality they have achieved almost nothing. Scientifically, there are better ways to measure the stress that humans are placing on the climate system than the growth of average global surface temperature — which has stalled since 1998..." And: "Because it sounds firm and concerns future warming, the 2°C target has allowed politicians to pretend that they are organizing for action when, in fact, most have done little. Pretending that they are chasing this unattainable goal has also allowed governments to ignore the need for massive adaptation to climate change." David G. Victor & Charles F. Kennel (2014) Ditch the 2°C warming goal, Nature 514, 30-31. This chimes with a Nature editorial in the same issue: "The politics and the science of climate change have long since parted company..." And: "The science, of course, can help to guide policy, as is explained in a Comment on page 30 on the absurdity of the 2°C target for global temperature rise..." Nature (2014) 'Warming up', vol. 514, p5-6.

- A (UK) Foreign and Commonwealth Office commissioned report has been published by Centre for Science and Policy at Cambridge University: Climate Change: A Risk Assessment with its lead author a former Government Chief Scientific Advisor and current UK Foreign Secretary’s Special Representative for Climate Change, David King, and sports a politically endorsing Ministerial foreword by the Rt. Hon. Baroness Anelay. Its principal conclusions are that we need to prepare for a warming of greater than 2°C: "On all but the lowest emissions pathways, a rise of more than 2°C is likely in the latter half of this century. On a medium-high emissions pathway (RCP6), a rise of more than 4°C appears to be as likely as not by 2150. On the highest emissions pathway (RCP8.5), a rise of 7°C is a very low probability at the end of this century, but appears to become more likely than not during the course of the 22nd century. A rise of more than 10°C over the next few centuries cannot be ruled out."

King, D., Schrag, D., Dadi, Z. & Gosh, A. (2015) Climate Change: A Risk Assessment. Centre for Science and Policy. University of Cambridge: Cambridge, Great Britain.

- It's 2015 and the world has passed 400ppm CO2. So, so much for my considered safe limit being below 400ppm.

- The feasibility or not of keeping warming to below 2 °C. have been echoed by a paper in Nature. Joeri Rogelj et al have calculated that the 2015 Paris Accord nations' intended greenhouse emissions (INDCs in climate policy speak) imply a median warming of 2.6–3.1°C by 2100AD. Substantial actions are required to maintain a reasonable chance of meeting the target of keeping warming well below 2°C.

Rogelj, J. et al. (2016) Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2°C. Nature vol. 534, pp631-639.

- The International Energy Association says that the challenges to keep warming below 2°C are immense, while the transformation in energy supply to meet the Paris Climate Accord's aspiration of keeping warming below 1.5°C is stark.

International Energy Association (2016) World Energy Outlook 2016. IEA: Paris.

- The WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin October 2017 from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the Global Atmosphere Watch reports that 2016 saw both the greatest annual rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and highest annual emissions on record. Meanwhile the The Emissions Gap Report 2017: A UN Environment Synthesis Report from the UN's Environment Programme concludes that the gap between atmospheric levels and emission and the reductions in emissions needed to ensure warming stays within the Paris Accord limit is now so great that much more is needed to be done: it "demonstrates why governments, industry and the

financial community can and must collaborate to provide the conditions that foster and fast-track innovative solutions. This is the only way to keep the global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees".

- Jeff Tollefson, in an article in the science journal Nature (2018), assesses the current rate of fossil carbon emissions and warming implications. He concludes that while the 2000-2016 growth in renewable energy has been remarkable, we need to do much more to limit emissions if we are not to break the UN COP Paris Accord goal of below 2°C warming by the year 2100: current policies could lead us to up to 3.7°C warming. There is a short summary/comment on this in this site's 2018 news page.

Tollefson, J. (2018) Carbon's future in black and white. Nature, vol. 556, pp422-425.

- Regarding threshold events, a paper came out in PNAS (2018) warning of the urgent need to avoid Earth system/climate thresholds as our current trajectory is taking us to a hot-house Earth. Crossing

such a threshold would lead to a much higher global average temperature than any interglacial in the past 1.2 million years and to sea levels significantly higher than at any time in the Holocene (the past 11,000 years). To avoid this, the paper says, will entail stewardship of the entire Earth System—biosphere,

climate, and societies—and could include (as the IPCC in its current report says) decarbonisation of the global economy.

Steffen, W., Rockstrom, J., Richardsorf, K. et al. (2018) Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1810141115.

- The IPCC's report, Global Warming of 1.5°C, explicitly states that limiting warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial (or 0.5 °C above early 21st century temperatures), compared to limiting warming to 2°C, offsets significant climate change costs. However to do this will require a drastic level of reductions from 2020. It says that a short delay in implementing a decarbonising strategy will lead to a temporary overshoot of 1.5°C warming but could still be within the 2°C limit. There is a comment on my 2017/8 news page.

IPCC (2018) Global Warming of 1.5 °C. IPCC, Geneva.

- The British Petroleum BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019 notes the mis-match between climate change goals and fossil fuel emission trends.

- Even if we agreed that from now on (2019) that there would be no new plans for new fossil fuel electricity generating stations and that all future car production would be electric (not fossil fuel), the existing fossil fuel energy infrastructure (that existing and already planned or under construction) would generate so much carbon emissions that we could not meet the 2015 Paris Accord goal of limiting warming to 1.5 °C.

Tong, D., Zhang, Q., Zheng, Y. et al, 2019, Committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure jeopardize 1.5 °C climate target. Nature, vol 572, p373-377.

- Our collective failure to act strongly and early means that we must now implement deep and urgent cuts. This report tells us that to get in line with the Paris Agreement, emissions must drop 7.6 per cent per year from 2020 to 2030 for the 1.5°C goal and 2.7 per cent per year for the 2°C goal. The

size of these annual cuts may seem shocking, particularly for 1.5°C. They may also seem impossible, at least for next year. But we have to try.

United Nations Environment Programme (2019) Emissions Gap Report 2019. UNEP: Nairobi.

- The increase in carbon dioxide from 2017 to 2018 was very close to that observed from 2016 to

2017, and practically equal to the average yearly increase over the last decade. For methane, the increase from 2017 to 2018 was higher than both that observed from 2016 to 2017 and the average over the last decade. For nitrous oxide, the increase

from 2017 to 2018 was also higher than that observed from 2016 to 2017. In short, the rate of greenhouse gas emissions is increasing (and not stablising let alone rate of greenhouse addition reducing) and so we are very far from absolute emissions reducing.

World Meteorological Organization (2019) WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin.World Meteorological Organization: Geneva.

- It's 2020 and a Nature article by authors from the NewClimate Institute, Cologne, Germany notes the price of a lost decade of inaction on curbing fossil carbon emissions. With the December 2009 COP 15 Copenhagen Accord (to which many nations did not sign up to but did accept it as advisory) the world would have had to halve the then fossil carbon emissions over the then next 30 years to 2040. However, since 2010 not only have emissions failed to decline, they have actually increased by14% (actually the 2008 - 2018 rise). This means that to keep warming below 2°C rise above pre-industrial even a greater, sharper degree of cuts is needed by 2030. Instead of a 14% increase in emissions from 2010, we need even the cuts from the new current levels.

Hohne N., den Elzen, M., Rogelj, J., et al (2020) Emissions: World has four times the work or one-third of the time. Nature. vol. 579, p25-28.

Doesn't look like it!

However that does not mean we should do nothing.

It is important to curb emissions to lessen warming as we are going to have to pay

increasing impact mitigation costs with greater warming.