|

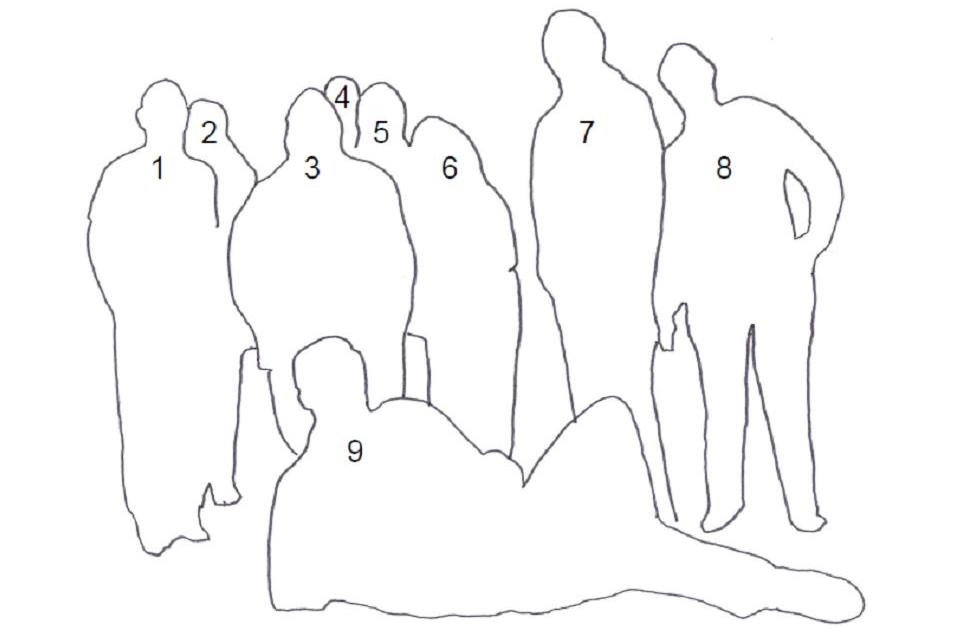

Graham (1982)

Graham (1982) Jonathan & Graham (2017)

Jonathan & Graham (2017)

(Background: Fellow 1st generation

PSIFAns - John Watkinson &

Anthony Heathcote.) |

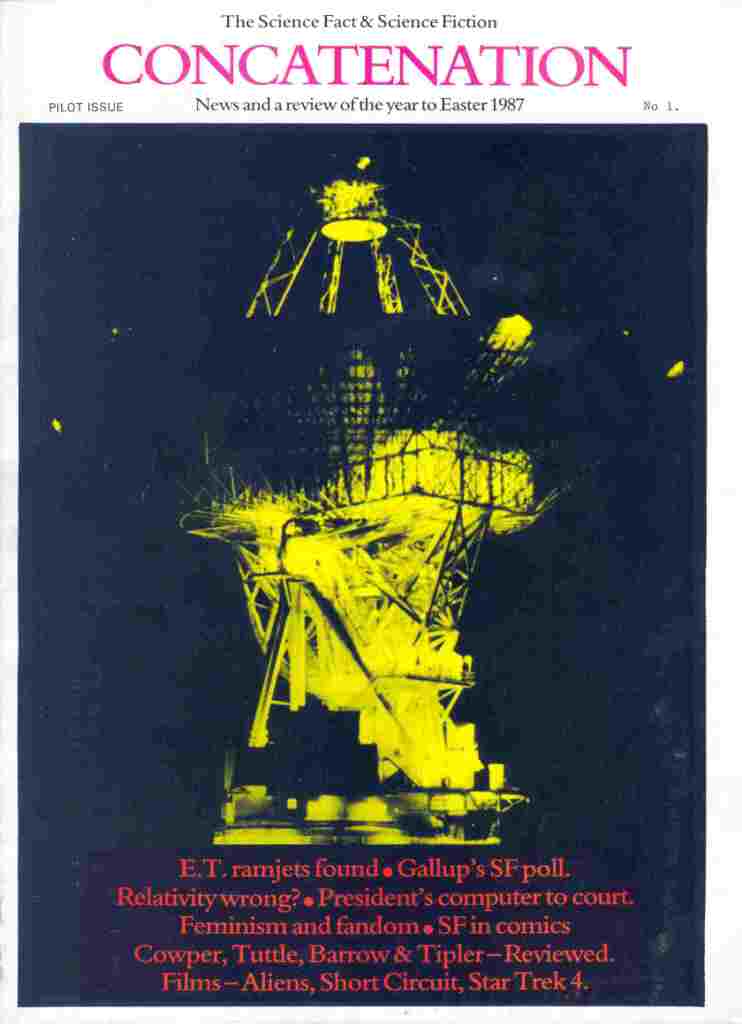

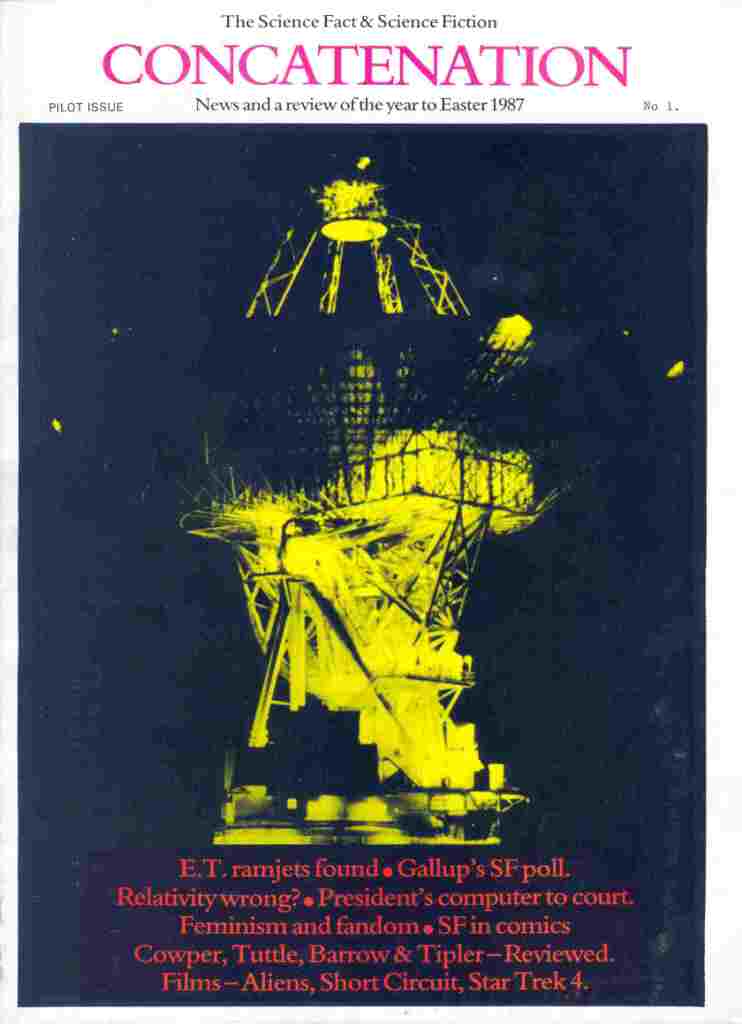

Concatenation Science Communication

Past news 2017/18

Christmas 2018 Graham Connor, physicist turned aerospace engineer, my longstanding compatriot

of over four decades and co-founder of our genre wing SF² Concatenation, passed away on Boxing Day.

I really don't want to go into any detail here right now save that he had not been well for several years, though I had hoped that

he had achieved some sort of stability. There's an obit over on

SF² Concatenation.

(And if you are reading this in the far future you may be able to find the Science Fact & Science Fiction Concatenation over at the British Library's Web Archive site.)

|

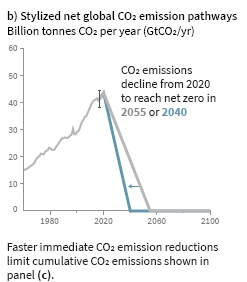

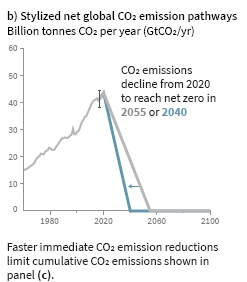

© IPCC 2018. The IPCC's 2018 Global Warming of 1.5 °C report highlights the degree and rate of change in carbon emissions that are needed to limit warming.

© IPCC 2018. The IPCC's 2018 Global Warming of 1.5 °C report highlights the degree and rate of change in carbon emissions that are needed to limit warming.

This almost makes my 2009 essay, Can we Beat the Climate Crunch?, an exemplar of modesty.

The faster reduction scenario reduces the chance of temporary 1.5°C overshoot. Slower reductions, with zero carbon emissions delayed to 2055, will see 1.5°C overshoot.

See graph below.

|

Autumn 2018 The IPCC has published its report on the need to limit warming to 1.5°C. The report has just come out and I have read its 'Summary for Policy Makers' (not the full report yet). I have to say how striking it is in the way it chimes with my own views as expressed in my climate change books (1998, 2007 & 2013) as well as my 2009 on-line essay Can we Beat the Climate Crunch?.

The new IPCC report, Global Warming of

1.5°C, explicitly states that limiting warming to

1.5°C above pre-industrial (or 0.5 °C above early 21st century temperatures), compared to limiting warming to 2°C, offsets significant climate change costs. However to do this will require a drastic level of reductions from 2020 (see the graph left). This very much chimes with my Can we Beat the Climate Crunch? essay written a decade ago albeit the IPCC and my essay express essentially the same thing with a different nuance.

My 2009 essay talks of the need to keep warming below 2°C with 2°C being the limit. But do note that back then I also said that this 2°C limit is "a 'comparatively safe' limit". Further, while the 2018 IPCC report talks of a 1.5°C limit it actually contemplates a temporary overshoot above 1.5°C but below 2°C (see the graph from the IPCC below).

|

|

The change in greenhouse gas emissions trends needed to meet the IPCC's report's aspirations is drastic (see graph above left). Well, back in 2009, I did say "it seems very likely (without a really major change in global human behaviour) that we will exceed our 'safe' 2ºC above pre-industrial level (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature) warming".

Of course, regardless how much the IPCC and I concur, talk is cheap: it is not a question of what the IPCC (or even little old me) says, but what our political leaders and global population do! Here, I am less optimistic and, importantly, I also warn of threshold events that take us through a climate transition. (Some call these 'tipping points' but for mathematical reasons I am not comfortable with that term.)

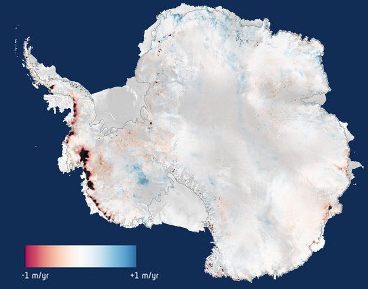

© IPCC 2018. IPCC (2018) Global Warming of 1.5 °C. IPCC, Geneva.

© IPCC 2018. IPCC (2018) Global Warming of 1.5 °C. IPCC, Geneva.While I have got you attention, and talking of threshold events, a paper came out a few months ago warning of the urgent need to avoid such thresholds as our current trajectory is taking us to a hot-house Earth. Crossing

such a threshold would lead to a much higher global average temperature than any interglacial in the past

1.2 million years and to sea levels significantly higher than at any time in the Holocene (the past 11,000 years). To avoid this, the paper says, will entail stewardship of the entire Earth System—biosphere,

climate, and societies—and could include (as the IPCC in its current report says) decarbonisation of the global economy. See Steffen, W., Rockstrom, J., Richardsorf, K. et al. (2018) Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1810141115.

Arctic summer, sea ice decline represents the source of a likely future climate threshold: a climate transition that is a leap to a new state of the Earth system. (See below.)

Arctic sea-ice decline is an example of a likely future climate threshold. As highly reflective Arctic, summer sea ice declines, so darker, sunlight absorbing open water is exposed. This leads to great warming and is a process behind what is called 'Arctic amplification' of warming. The concern is that once this reaches a critical point the warming of the Arctic region in the summer will warm considerably. This may have other impacts, such as on the jet stream, so affecting mid-latitude climate regimens.

|

|

|

Summer 2018 Break in the Peak District. A fair bit of walking, much chat, great food, wonderful, local real ale and, to round days off, catching up with the Hugo shortlist for Dramatic Presentation. Made it to top of Mam Tor, visited Druid's Cave (or 'Droids Cave' as it might be re-named) with its stone carved cave, stairs, chairs etc: a little surreal (see picture left). One of the visit's highlights was the village of Eyam which, among other things, is noted for having cut itself off from the world in 1665 as a self-imposed quarantine measure to prevent the spread of the Black Death. The village's other historical human ecology attractions include a series of connected troughs that were part of one of the first communal water delivery services.

|

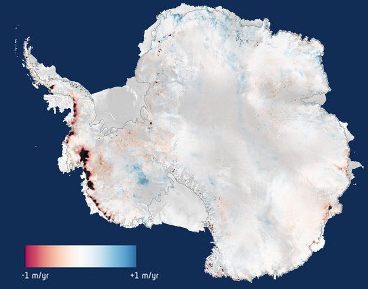

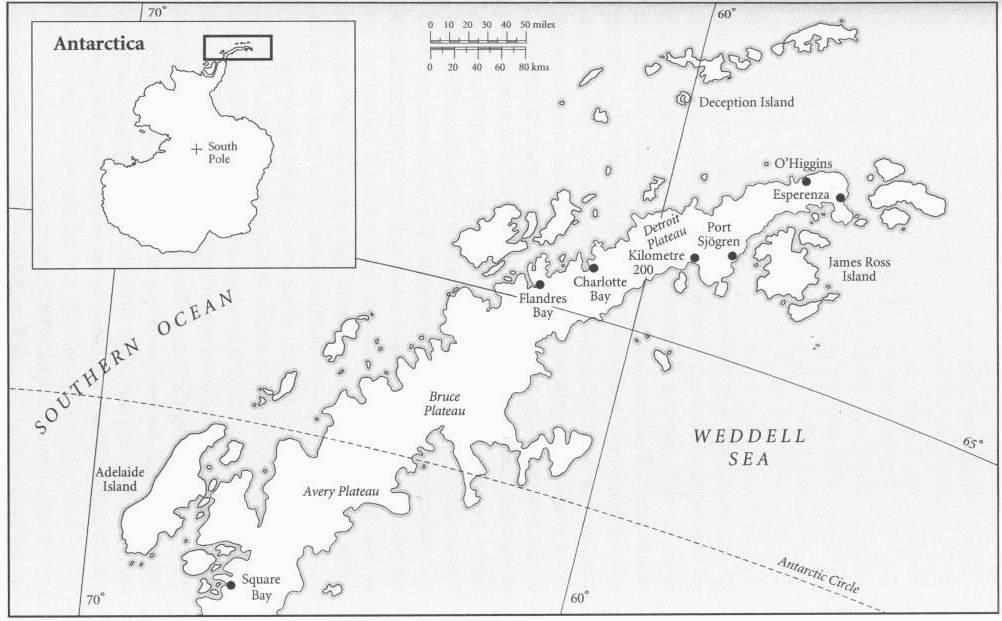

Rate of Antarctic ice volume change

Rate of Antarctic ice volume change

2010-2013.

|

Summer 2018 Antarctic ice melt increases. Another of a slew of key climate and Earth system science papers this summer. The UN IPCC forecasts ignore long-term feedbacks (such as ice sheet melt) as we cannot see into the future how some aspects of the Earth system will respond in the long term. Current IPCC forecasts for sea-level rise are based on a combination of current observations and computer models. The latest news comes from the ESA–NASA Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise. In brief, it has found that the rate of Antarctic melt has more than tripled between 1992 and 2017! This is not offset by greater ocean evaporation in our warming world freezing as ice on East Antarctica. (See The IMBIE team, 2018, Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature, vol. 558, p219-220.)

|

|

|

At this point I wish I could knock together the heads of a peer-reviewer and a commissioning editor of a publisher (whom I'll keep nameless) who rejected what would eventually become my 1998 book Climate and Human Change: Disaster or Opportunity? with another publisher. The book was criticised by the academic peer-reviewer, hence rejected by the commissioning editor, for stating that the last interglacial's peak was warmer than our present day and the sea-level higher. This despite my citing academic references in support of that contention. Jump forward to 2007, or better still 2013 and the 2nd edition of Climate Change: Biological & Human Aspects from Cambridge University Press, and I noted (p335) that during the last interglacial (roughly some 100,000 years ago) there were rapid jumps in sea level rise of over 3 metres a century! (See also Blanchon et al., 2009, Nature vol. 458, p881-4.) So this summer's news from ESA–NASA Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise came as no surprise to myself.

So how come I predicted this a couple of decades ago? Well, I have no crystal ball. The answer is that I do not rely on computer models (though they are interesting) but palaeo-data from the geological record. This clearly shows that during the glacial-interglacial transition to our warm Holocene that the sea-level rose faster than the IPCC predicts for this 21st century, yet the rate of warming back then was an order of magnitude slower. The inference is obvious. Indeed, even if it was not, those reasonably versed in the science literature will recall that three years ago we had more than an inkling that the Antarctic was melting faster (see picture above).

All in all, important news as this is, there are no surprises here. What it does emphasise is that we do need to move to a more tougher target than that of the 2015 UN Paris Accord.

|

Human brain size as illustrated by Concatenation's physicist Graham as he was back in 1989. Next to him is a neolithic skull from Jersey, Channel Isles.

Human brain size as illustrated by Concatenation's physicist Graham as he was back in 1989. Next to him is a neolithic skull from Jersey, Channel Isles.

(Graham is the one of the left.)

|

Summer 2018 Climate change cost benefit + Climate human brain-size evolution + Earth's first tall mountain ranges: It's a bumper issue of Nature. As one of my former IoB Biomedical Sciences Committee member, the biochemist

P. Campbell, once said: "Once you've taken all the cardboard out, Nature's actually quite a good read." I have to say I spend one to three hours a week reading the science journal Nature (not counting the time re-visiting papers when working on a project) and that's quite a commitment especially given that I spend less than an hour skimming the contents online and downloading abstracts or papers from Science, PNAS, PLOS One, Royal Soc. Trans (B), etc). But it's not the news pages or the excellent N&V review pages, interesting as they are, that suck up much of the time: it's the research papers of interest. Fortunately, most issues there's only one or two of these. However the end of May saw an issue with three key research papers and two accompanying News & Views reviews: five articles necessitating serious attention. So without further ado, here they are:-

|

|

|

Limit greenhouse emissions so warming stays below Paris Accord warming more ambitious target of limiting warming to below 1.5°C compared to an IPCC business-as-usual 4°C warming (RCP8.5) avoids a 30% or more loss of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The researchers find that 71% of countries -- encompassing about 90% of projected global population -- exhibit a >75% chance of experiencing positive economic benefits at 1.5°C relative

to 2°C. They do this by combining a century's worth of historical evidence (economic and climatic) with national-level climate and socioeconomic

projections to quantify the economic damages associated with the United Nations (UN) targets of 1.5°C and 2°C global warming, and those associated with current UN national-level mitigation commitments (which together approach 3°C warming). The poorest countries benefit the most. See Burke, M. et al, 2018, Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets. Nature, vol. 557, pp549-553. There is also a News & Views comment article the same issue.

Ecological pressures were the principal driver of evolution increasing human brain size. The human brain is unusually large: it has tripled in size from Australopithecines to modern humans. There is a theory (for which I have some sympathy) that the Quaternary (past two million years) series of glacials and interglacials caused repeated ecological change that spurred hominid evolution. But social (cooperative groups have better survival prospects) and cultural (passing on knowledge across generations) dimensions also confer benefits. Undoubtedly all play a part in human evolution, but which did the most? This research takes a different approach to previous studies in that it looks at the metabolic and physiological cost of brain development (large brains need good nutrition). It merges elements of metabolic theory, life-history theory and differential games to obtain quantitative predictions for the evolution of brain and body size when individuals face ecological and social challenges given metabolic costs of the brain. Their model predicts the evolution of

adult Homo sapiens-sized brains and bodies when individuals face a combination of 60% ecological, 30% cooperative and 10% between group

competitive challenges, and suggests that between-individual competition has been unimportant for driving human brain-size evolution. Environmental factors, according to this study, corroborate the view that ecological change (instigated by climate change), was critical. See González-Forero, M. & Gardner, A., 2018, Inference of ecological and social drivers of human brain-size evolution. Nature, vol. 557, pp554-7. There is also a useful review article here.

The final paper relates to the new area of Earth System Science I'm currently working on...

The first emergence of large and continents with high mountain ranges 2.5 billion years ago triggered the modern hydrological cycle and spurred the oxygenation of the Earth. This study looks at three oxygen isotopes (O16, O17 and O18) in sediments across 3.7 billion years. In essence, evaporation transports lighter isotopes more easily than heavier ones and so a triple oxygen isotope analysis provides a handle on how much rain falls on lend (ending up in sediments at the ends of rivers). This work reasonably convincingly shows that the hydrological cycle changed markedly after 2.5 bya. The idea is that it took a while (a few Wilson cycles) for continents to develop substantial foundations (cratons) on which tall mountains could stand, and these mountains alter the way water falls on land, and enhances nutrient erosion which helped early oxygenic cyanobacteria that transformed the Earth's atmosphere from one that was devoid of oxygen to one with a low, roughly 2%, oxygen content. See Bindeman, I. A., et al, 2018, Rapid emergence of subaerial landmasses and onset of a modern hydrologic cycle 2.5 billion years ago. Nature, vol. 557, pp545-8.

|

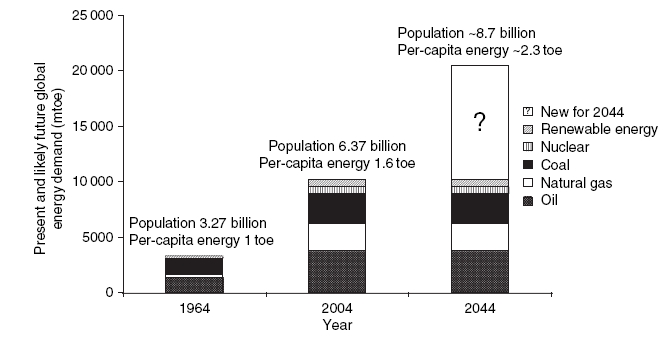

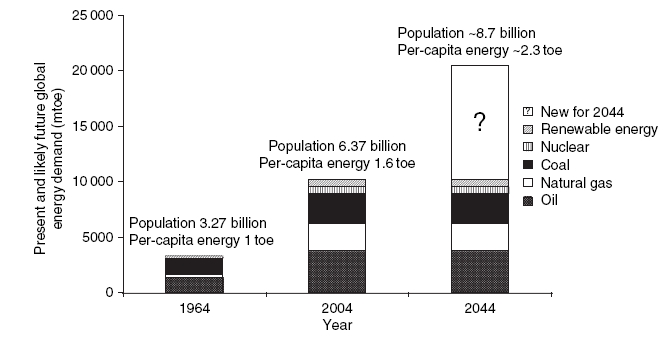

This graph I prepared in 2006 for my 2007/2013 climate change books. There is well over the same amount of fossil fuel that we have burned to date still in the ground. Should recent trends 1964 – 2004 continue (as they broadly have to date, 2018) by 2044 global energy demand will double that seen in 2004 (see above diagram from Climate Change: Biological and Human Aspects by Jonathan Cowie). And should we then double atmospheric carbon dioxide (which if we follow current trends we will do well before the end of the second half of the 21st century), then warming will exceed 2ºC above pre-industrial levels!

This graph I prepared in 2006 for my 2007/2013 climate change books. There is well over the same amount of fossil fuel that we have burned to date still in the ground. Should recent trends 1964 – 2004 continue (as they broadly have to date, 2018) by 2044 global energy demand will double that seen in 2004 (see above diagram from Climate Change: Biological and Human Aspects by Jonathan Cowie). And should we then double atmospheric carbon dioxide (which if we follow current trends we will do well before the end of the second half of the 21st century), then warming will exceed 2ºC above pre-industrial levels!

1950 actual and 2099 forecast January temperatures from the 2015 NASA data made publicly available. I could have presented June data but, with most of the Earth's land in the northern hemisphere (which has summer in June), that makes the warming seem more pronounced and I'd hate to scare the horses (but do note what happens in the southern hemisphere's January summer). Nonetheless, much of Britain will in 2099 likely experience frost free winters. In turn, one ecological impact of this will be increased surviving agricultural and garden pests.

1950 actual and 2099 forecast January temperatures from the 2015 NASA data made publicly available. I could have presented June data but, with most of the Earth's land in the northern hemisphere (which has summer in June), that makes the warming seem more pronounced and I'd hate to scare the horses (but do note what happens in the southern hemisphere's January summer). Nonetheless, much of Britain will in 2099 likely experience frost free winters. In turn, one ecological impact of this will be increased surviving agricultural and garden pests. |

Spring 2018 Fossil carbon emission trends suggest we will greatly miss keeping global warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels says an article in the science journal Nature. The 2015 UN COP Paris Accord aims for nations to keep greenhouse gas emissions below the level that would warm the world by 2°C above pre-industrial levels, but the new Nature article suggests that we are likely to miss this by nearly a couple of degrees: that is twice the maximum warming the UN wants us to keep within. Regulars to this site may remember that nearly a decade ago (back in 2009) I wrote an essay -- 'Can We Beat The Climate Crunch' -- to answer the most common questions I've been asked when lecturing and giving talks. That essay was prescient in a number of ways, including my estimate of the maximum 'safe' level of warming as this chimed with the subsequent UN COP Paris Accord six years later. (Though it should be noted that my 2°C above pre-industrial levels 'safe' limit is an absolute limit whereas the Paris Accord limit only relates to warming up to the year 2100: warming will continue after that date due to system inertia as well as any future, possibly lower-level of continued greenhouse emissions.) But I also concluded that it seems very likely (without a really major change in global human behaviour) that we will exceed our 'safe' 2ºC above pre-industrial level (or 1.2ºC above the Earth's 2006/7 temperature) warming. A conclusion that incidentally years ago caused one senior UK science advisor to give me chastisement... Yet, since 'Can We Beat The Climate Crunch', at least once a year from 2010, others have voiced similar conclusions, and these I cited at the essay's end in a 'latest news' list.

Which brings us up-to-date and the latest article in Nature by Jeff Tollefson. He notes that the 2014-2016 halting in emissions -- which optimists and some politicians had thought might signal the success of climate change policies -- was in fact due to the economic slow-down in China. In 2017 China recovered a little while India saw strong growth and this served to push up emissions. Meanwhile, the rate of emission reductions in the US and European Union (including UK) reduced, possibly due to most of the low-hanging fruit reduction possibilities having already been picked.

But it is not all bad news. Renewable energy between 2000 to 2016 has grown markedly, and far more than many suspected was possible. The problem is (the article's accompanying data graphs suggest) that renewable growth, remarkable as it has been, needs to increase 7 or 8 fold to offset the 2000 to 2016 rate of growth in fossil carbon emissions should that medium-term growth trend continue into the long-term. That would then keep emissions steady. Further, to get actual reductions in carbon emissions, the rate of renewable growth needs to increase to over 12-fold by 2020 if we are to keep within the Paris Accord, 2°C limit. The question you may want to ask yourself is how likely is this without a really major shift, and hardening, of climate change policies? (And perhaps even a boost to nuclear power that has globally flat-lined so far this century?)

The reference for the article is: Tollefson, J. (2018) Carbon's future in black and white. Nature, 556, 422-425.

(As a personal addendum, I should emphasise that all the above relates to warming up to 2100 (not beyond) and that the climate sensitivity (or equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS)) estimates used for this ignore Earth system sensitivity (ESS).)

|

|

|

Spring 2018 April's Geoscientist has an online special on the IPCC by myself. Work on the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) sixth assessment report (AR6) is now beginning. The IPCC arguably, I contend, needs to consider three things.

i. Cut down on bloat. Successive assessments have grown in size, so much so that only the very dedicated are likely to read it all.

ii. Compare previous analogue scenario forecasts so we can see whether the IPCC's forecast scenarios are becoming more optimistic or pessimistic.

iii. And to do that it needs to standardise its scenario base years for warming and its models' forecast start points.

Many thanks go to Geoscientist for letting me flag up these issues. The original online special can be accessed at www.geolsoc.org.uk/ Geoscientist/April-2018/A-case-of-the-bloats (and an archive PDF version on this site here).

|

|

|

April's Geoscientist also contains a letter from myself concerning the society's data protection policy for its Fellows in light of the new European General Data Protection Rules (GDPR), or Regulation (EU) 2016/679, that comes into force this May. I don't think it has been since my Institute of Biology days, and its journals, have I had more than one contribution published in a single edition of a learned publication, hence this website post. The letter is archived as a PDF here.

|

Biologist's smaller, two-colopur cover format of the 1980s.

The first issue (1990) of the larger A4 colour cover format.

|

Spring 2018 R. J. (Sam) Berry FRSE CBiol FIBiol passes aged 83. Sam was a whole-organism, polymath biologist into ecology, genetics, evolution and also science-religion relationships. Sam Berry was prominent among the communities relating to all these areas. Testimony to this last is that he was president from 1983 to 1986 of the Linnean Society and then 1987 to 1989 president of the British Ecological Society (BES). He was also a a lay member of the Church of England's General Synod and president of Christians in Science. Though I worked with many from both the BES and the Linnean between the late 1980s to early 2000s, and indeed became a BES member myself in the early 1990s, this is not how I knew Sam. Sam was the Chair of the Biologist editorial board throughout the 1980s through to the end of 1992. And so Sam was in situ with Biologist when I started with the Institute of Biology (now re-branded as the Royal Society of Biology) initially as its Publications Manager. Back then Biologist was a fully peer-reviewed journal with articles covering the breadth of the biosciences and sporting a circulation that exceeded 16,000; few peer-reviewed science journals see that sort of circulation. (Subsequently, long after I moved from journal publication to science policy, it ceased peer-reviewing in 2002 and formally became a magazine in 2011.) And so, as Publications Manager, serving the journal's editorial board as its secretariat with Sam at its helm, I was able to begin to see Britain's bioscience landscape. Indeed, taking some of the weight off the journal's then executive editor (the diligent Helen Johnson), Sam began to give me the job of securing some of the journal's editorial content. One of my first such jobs was to get the rights for a piece from the (then controversial among some biologists but not Sam) James Lovelock. And later under Sam, I managed a Biologist series of articles on 'Chaos in Biology' (chaos in the mathematical sense) with the series' own invited specialist advisor, Prof. Bob May. This last was one of the rather useful contacts I made through Sam as not only did Bob May himself go on to be President of the British Ecological Society, but later still the Government's Chief Scientific Advisor and even later still President of the Royal Society: personal contact, as opposed to simply a name on documents, with these last two positions was rather helpful in my time as the Institute of Biology's Head of Science Policy and Books. So when I say that Sam enabled me to see and make sense of Britain's bioscience landscape, this really was something central in my early career and personally more important to me in his term at the helm of Biologist compared to other things, such as being Publications Manager revamping the journal's format during Sam's tenure.

Biologist readers of the 1980s will remember that in addition to fine review papers on a broad range of topical bioscience concerns and developments, Biologist also ran series of articles including: 'My week as... [specialist bioscientist], 'Exploited plants', 'Exploited animals', 'Famous laboratories', 'Who was... [named bioscientist of yesteryear]', and 'Briefings [on breakthrough scientific discoveries/techniques and bio-legislation]'. During Sam's time Biologist became -- membership surveys reveal -- by far the clear forerunner benefit of Institute membership; streets ahead of any of the others. That was very largely Sam's doing.

|

|

|

Spring 2018 Mass extinctions: Understanding the world's worst crises. More CPD attending the Geological Society's annual Lyell meeting (programme archived here). This is one of the highlights of the Geological Society calendar and named after the Charles Lyell, the author of Principles of Geology which basically supported Hutton's idea that the processes that are altering the land, and geology today, are the same as those that operated in the past: the principle of uniformitarianism. This year's Lyell meeting was on mass extinctions. And there are more extinction events that most realise: Carnian Pluvial Event anyone? The bottom lines of the meeting included that: many mass extinctions are associated with carbon isotope excursions; and that mercury could be a geological indicator of past volcanic activity albeit one interpreted with caution as life cycles mercury so mass vegetation decay can also give a signal.

Despite there being much good science, I actually came away with less notes than I usually do. The organisers' approach this year was to cram in as many papers as possible. And so we had a continual train of presentations, each only 15 minutes long with no time allowed for Q&A (well, some presentations had time for one question) or 5 minutes handover. Added to which there was no session or all-day summary panel and Q&A. In short there was no opportunity to tease out themes and define a coherent narrative. The impression I got chatting to others, including some of the speakers, over coffee, tea, lunch and post-symposium reception, was that I was not alone with such concerns. Alas it was a triumph of lack of style over substance; I'm certainly not in favour of factory farming science. (That a quarter of the presentations came from one the convenor's university itself was almost telling.) Had the symposium been spread over two days this could have been both an informative and an influential event. (Indeed, it might even have led to insights into the long-term impacts of our current, global warming CIE.) But do not let my comments on this year's Lyell meeting put anyone off Geological Society events: most are much better planned than this.

|

|

|

Spring 2018 Elegant climate sensitivity calculation made. New key climate change paper. Every now and then I like to post news of a key climate change paper: given the last edition of my Climate Change: Biological & Human Aspects was back in 2013, there are subsequent key works not covered in that book of likely interest to students (and other parties). Climate sensitivity is in essence (as commonly used) a measure of the global warming that would result of a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide. However estimates vary. This is because that while measurements of the energy absorbed in laboratory conditions lead to a calculation of roughly 1°C rise for a doubling, in the real world such warming also affects the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere (water vapour itself being a greenhouse gas) and other feedbacks. And so (doubling) climate sensitivity (more accurately described as 'equilibrium climate sensitivity') is in real life greater than 1°C. (A short term perspective of the warming after a year or so is known as the transient climate response (TCR) and a medium-term response as equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS), while a longer-term response (a few centuries) is known as the Earth system sensitivity (ESS).) The IPCC's 5th Assessment (AR5) in 2013 gives a climate sensitivity (ECS) range of between 1.5°C and 4.5°C, and this range in turn leads to a key part of the uncertainty in the IPCC's scenario warming forecasts. So what to do?

British climate researchers Peter Cox, Chris Huntingford and Mark Williamson, have come up with an elegant way of getting a better handle on the problem to determine the equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS). First, what they did was to use a number of different climate models (that each do things slightly differently) and see how over a small amount of warming each model's climate variability changes (rather than looking at warming per se). Second, using these results they developed a metric (based on a mathematical equation) that links global temperature variability with climate sensitivity. Third, they then related this to the real world and this could be done in two ways. First, their metric could also be used to calculate climate sensitivity (ECS) from historical real-world variability and, second, they could plug in different theoretical climate sensitivity values into various computer models and see which values enable the models to simulate the real historic climate variability we see in the meteorological record.

Having done all this, the researchers conclude that the probability of ECS being less than

1.5 degrees Celsius to less than 3%, and the probability of ECS exceeding 4.5°C to less than 1%. Using 66% confidence limits (equivalent to the IPCC ‘likely’ range) they calculate that climate sensitivity (ECS) is between of 2.2 - 3.4°C, with a central estimate of 2.8°C. While still a range of over a degree, it is a lot better than the IPCC's current range.

The reference for the researchers' paper is: Cox, P. M., Huntingford, C. & Wlliamson, M. S. (2018) Emergent constraint on equilibrium climate sensitivity from global temperature variability. Nature, vol. 553, p319-322. There is also an informative, open access, explanatory piece on the work in the same issue of Nature: Forster, P. (2018) Homing in on a key factor of climate change. Nature, vol. 553, p288 - 289.

|

Satellites can be used to look down on

Satellites can be used to look down on

the top of the Earth's atmosphere and so

exactly measure the energy absorbed and

reflected: its energy budget. © European

Space Agency and used here under limited, non-commercial, fair use. |

Autumn 2017 Global warming could be warmer according to a new analysis. Patrick Brown and Ken Caldeira, from the Department of Global Ecology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford, US, have looked at coupled atmosphere–ocean–land global climate models top-of-atmosphere energy budget and satellite observations as to what is really happening. They then took this real data and tweak climate computer models so that they reflected it. They looked at many models for various UN IPCC climate scenarios and 37 models for the greatest warming. They found that warming under what is effectively business-as-usual emissions was about half a degree Celsius warmer than the IPCC concluded in its most recent (2013) Assessment: 4.8°C rather than 4.3°C for the year 2090. If this work is corroborated, then it is a significant increase in the warming estimate since the IPCC's 2007 report (but still within the rather wide error-range given in the IPCC's first (1990) Assessment). What this means is that even greater emission reductions will be needed than the 2015 Paris Accord afford if warming is to be kept below 2°C. (See Brown & Caldeira, 2017, Greater future global warming inferred from Earth’s recent energy budget, Nature, vol. 552, p45-50.)

|

|

Now, I have long since considered that the UN's IPCC scenario estimates for warming to be underestimates! Let me be clear, this is not because I peddle doom and gloom, but for two very good reasons. First, I have read the Working Group I Assessment reports carefully (not to mention am aware of the supporting literature) and so I know of the IPCC's caveats. For example the IPCC (openly) ignores long-term feedbacks (there are many unknowns here and so it is best to ignore them until they can be more accurately discerned): to see this, all you need do is download the Working Group I chapters from the IPCC website and word search 'long term' and you'll find a many mentions all relating to this caveat. Second, I have read the palaeoclimate academic literature and there is a clear mismatch for both warming, as well as sea-level rise estimates, between many palaeoclimate research papers and the IPCC's present and near-future warming estimates. This mismatch is due the IPCC's scenario estimates being based on artificial scenarios that have the aforementioned caveats, while palaeoclimatic proxy data is based on reality: the real Earth system, not models.

What Patrick Brown and Ken Caldeira have done helps partly address this second, mismatch, category.

Most climate models focus on the lower atmosphere for their outcomes as that is where we humans live (even if they include aspects of the upper atmosphere in their calculations). Models typically use a range of assumptions and so get a range of results. Put very simply (as researchers are more sophisticated than this), where within models using different assumptions, and between different models (again using a range of assumptions), there is agreement the greater confidence is given to the models' common scenario forecast. What Patrick Brown and Ken Caldeira have done is to constrain the models' assumptions by replacing one category of assumptions (the Earth's energy budget at the top of the atmosphere) with 15 years' worth of real-life data from the Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) satellite observations. The results, when plugged into the IPCC scenario projections, give greater warming. If Patrick Brown and Ken Caldeira's work is validated before the next IPCC Assessment's literature cut-off date, then expect the next IPCC Assessment's scenario projections to be discernibly greater than the past 2007 and 2013/4 Assessment reports.

|

|

|

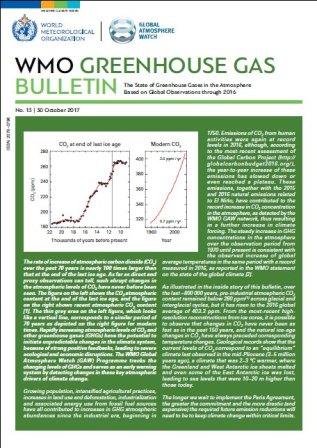

|

Autumn 2017 There has been a record surge in atmospheric carbon dioxide while the ability to reduce emissions has declined. It is a conflation of different bad news on the greenhouse front. i) Emissions of CO2 from human activities were again at record levels in 2016 at 403.3 parts per million. (In 2012 the first monitoring station recorded levels above 400ppm as part of the annual fluctuating cycle. Then in 2015 the global average level reached 400ppm. And in 2016 no part of the annual cycle fell below 400ppm.) ii) These emissions, together with the 2015 and 2016 natural emissions related to El Niño, have contributed to the record annual increase in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere. Finally, iii) The gap between the levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide and the reductions needed to reduce the potential for warming to so-called 'safe' limits has never been greater the UN warns.

The Paris Agreement adopted in 2015 set the specific goal of holding global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius (°C) compared to pre-industrial levels, and of pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C. Yet while a shift in technology and investment has in recent years demonstrably shown the potential to reduce emissions, such is the marked existing energy trend – with fossil fuels and cement production still accounting for about 70% of greenhouses gases and fossil carbon some 88% of global energy production – that the gap between the levels of emissions and the reductions needed is at a record high. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), recommends that there is an urgent need for accelerated short-term action and enhanced longer-term national ambition, if the goals of the Paris Agreement are to remain achievable! (See UNEP, 2017, The Emissions Gap Report 2017: A UN Environment Synthesis Report and WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 13.)

All this sadly echoes the appraisal made in my 2009 essay Can we beat the climate crunch (and specifically 'Can we avoid this threat of serious warming?') whose sentiments in turn were subsequently reflected by several others. Which, though I say so myself, does make the science in my climate change text all the more relevant.

|

|

|

Autumn 2017 The Prisoner's half-century celebrated in real ale. One of my all-time favourite television shows, The Prisoner, had the 50th anniversary of its first broadcast celebrated this September. And in Tamworth they were marking the occasion with a local CAMRA (CAmpaign for Real Ale) real ale festival. So, with real ale being one of my favourite occasional indulgences, it was a short hop across into the West Midlands. I normally am a north-south kinda guy to London and Concatenation's sub station, but we do actually have not bad east-west rail connections (well, off-peak at least) which make for a low, fossil carbon day out.

You can see the first episode of The Prisoner here - of which the first five minutes gives you the set-up - www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lo4HOmqd9fo.

Be seeing you.

|

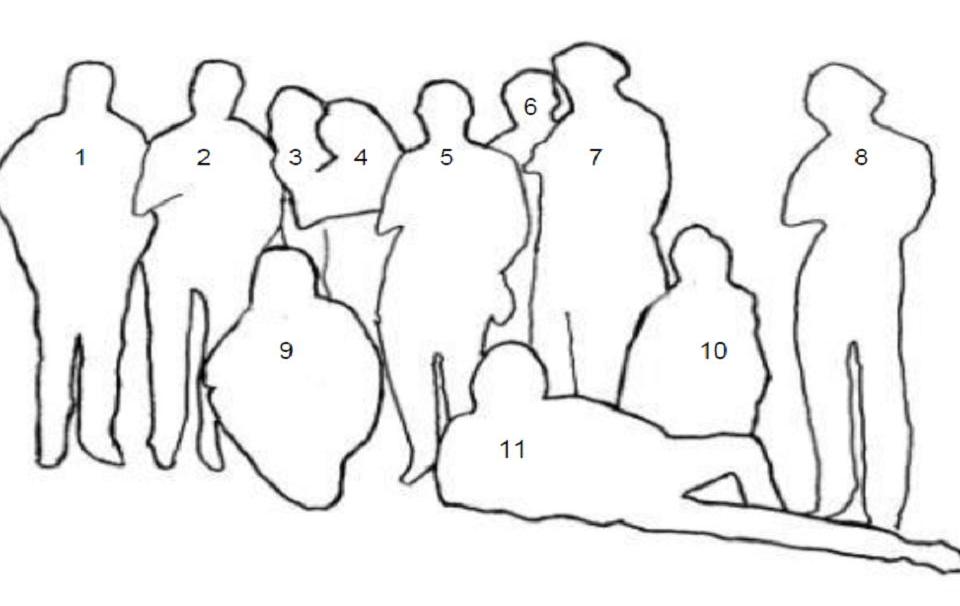

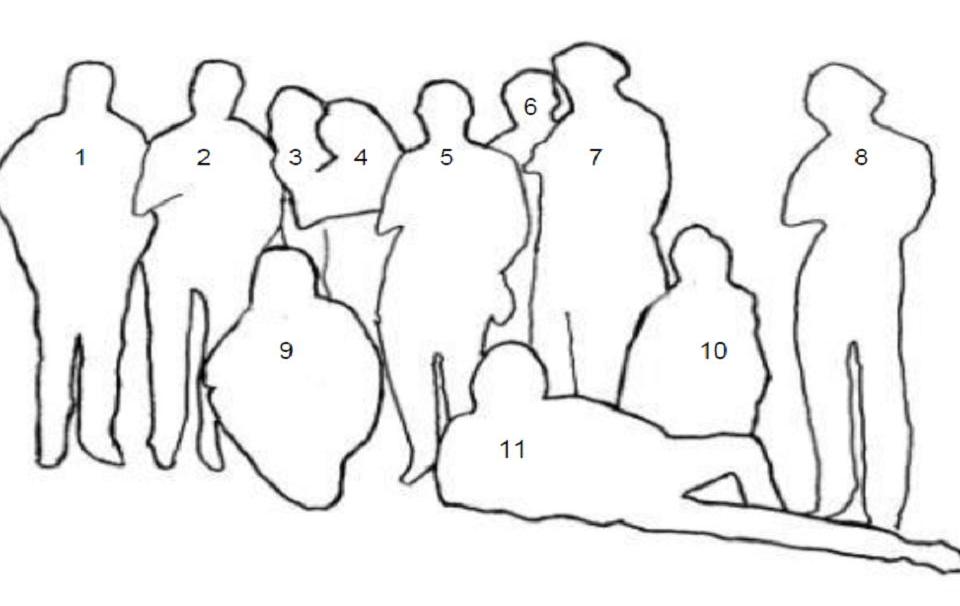

The original BECCON committee in 1980

The original BECCON committee in 1980

From left standing: 1, Peter Tyers;

2, Bernie Peek; 3, Mike & 4, Kathy

Westhead; 5, Brian Ameringen; 6, Roger Perkins; 7, Charles Goodwin; 8, John

Stewart; 9, Anthony Heathcote; 10, Roger

Robinson; and 11, Jonathan C. The original BECCON committee in 1980

The original BECCON committee in 1980

who ran three biennual London region

conventions (1981,'3 & '5) before running

the 1987 British national SF convention,

that year's Eastercon, BECCON '87.  The original BECCON 1981 committee 36

The original BECCON 1981 committee 36

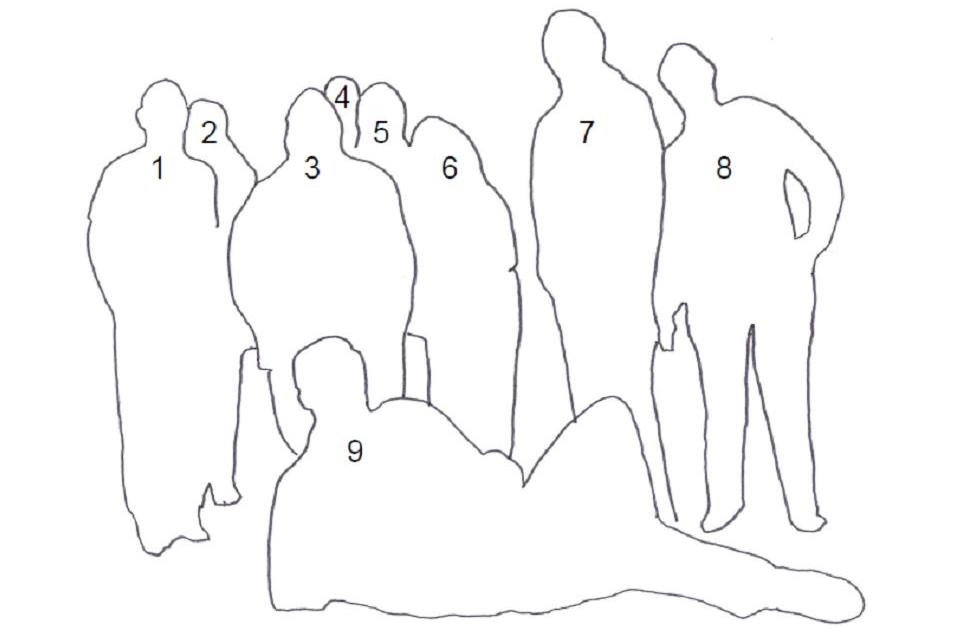

years on in 2017 with much grey. From left standing: 1, Brian Ameringen;

From left standing: 1, Brian Ameringen;

2, Caroline Mullan; 3, Roger Robinson;

4, Arthur Cruttendon; 5, Mike and 6, Kathy

Westhead; 7, John Stewart; 8, Anthony

Heathcote; and 9, Jonathan Cowie.

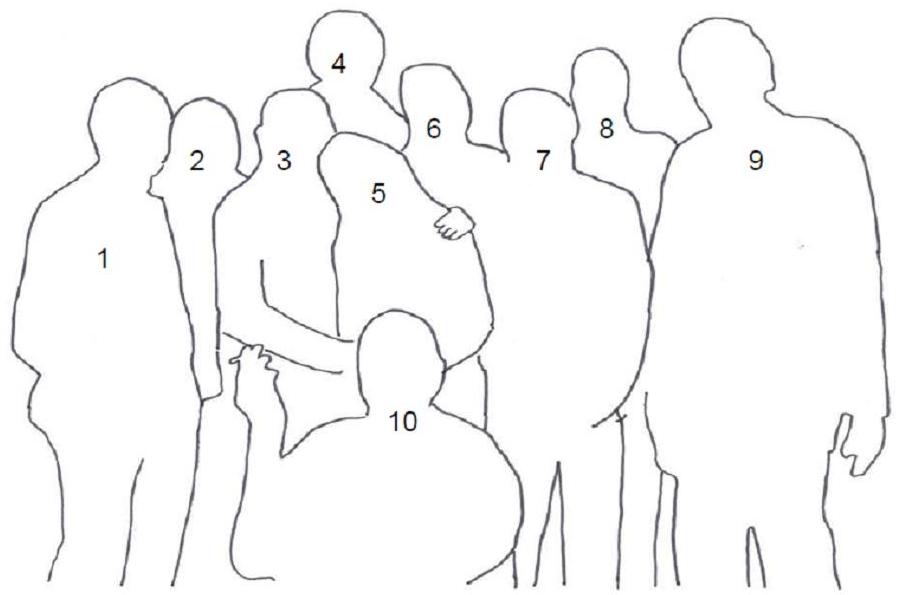

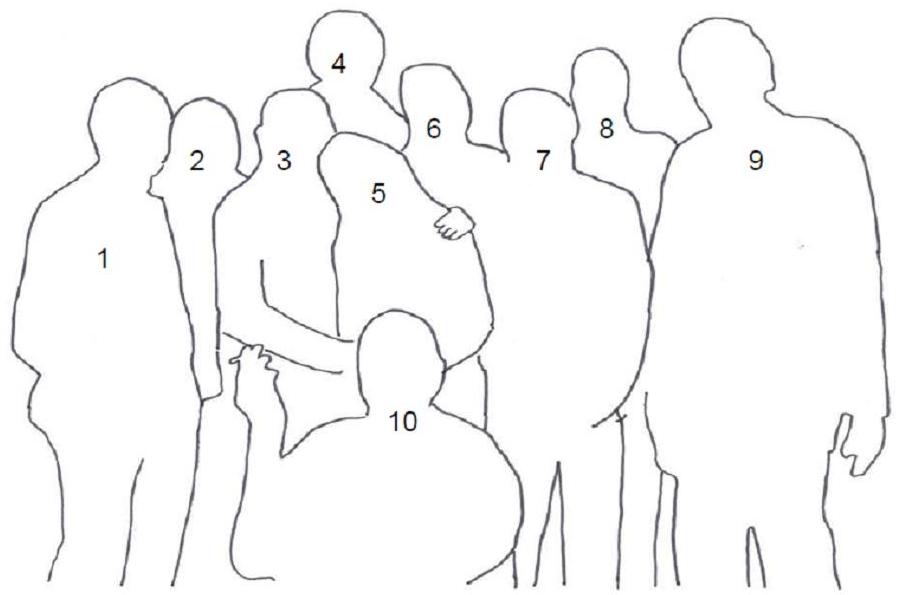

. The original BECCON 1987 committee

The original BECCON 1987 committee

plus some support staff now in 2017. From left: 1, Anthony Heathcote;

From left: 1, Anthony Heathcote;

2, Caroline Mullan; 3, Mike Westhead;

4, John Stewart; 5, Kathy Westhead;

6, Roger Robinson; 7, Brian Ameringen;

8, Arthur Cruttendon; 9; Jonathan Cowie;

10, Graham Connor. The front cover of the programme souvenir book. Jonathan C. was the committee member responsible for print farming (commissioning) and the SF aficionados Charles Partington with Harry Nadler on plate-making, did the actual printing. It was the first Eastercon souvenir book to have a full-colour cover. The cover features characters from Keith Roberts' books: Keith was one of that year's Guests of Honour.

The front cover of the programme souvenir book. Jonathan C. was the committee member responsible for print farming (commissioning) and the SF aficionados Charles Partington with Harry Nadler on plate-making, did the actual printing. It was the first Eastercon souvenir book to have a full-colour cover. The cover features characters from Keith Roberts' books: Keith was one of that year's Guests of Honour.

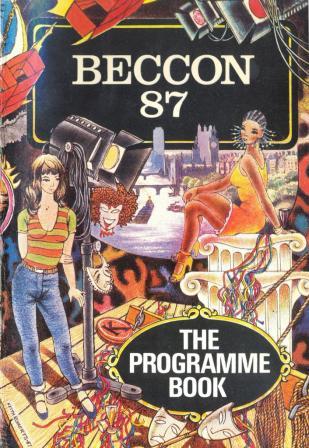

The artwork was by Keith. The cover of SF² Concatenation's first edition 30 years ago, back in our print days.

The cover of SF² Concatenation's first edition 30 years ago, back in our print days. |

Summer 2017 It was 30 years ago that the Science Fact & Science Fiction Concatenation was born. SF² Concatenation began as one of the 'extras', a science and fiction news and reviews magazine at Britain's 1987 national SF convention, called that year BECCON '87. (For reasons too lengthy for here, this stood for BECCON's EasterConCONvention.) BECCON '87 was itself held on the 50th anniversary year of the World's first SF convention which makes this year (2017) the 80th anniversary of that initial event. SF² Concatenation was only meant to be a one-off, but then life threw one of its curves (including it attracting sufficient advertising for decent production) and so it continued as a print magazine into the 1990s before migrating to the internet just prior to the millennium's end. Anyway, to mark this anniversary a dozen involved with the organisation of BECCON '87 and some of their partners, gathered at a Bedfordshire rural hostelry for a bit of a reunion, catch-up and a reminisce.

The 1987 Eastercon was itself a rather difficult event to run. One problem was that we simply did not know how many would attend: 1987 was also to be the year of Britain's third World SF Congress (Worldcon) and we did not know whether this would make more people attend the Eastercon or (because folk might choose one over the other) less. As it happened some 700 attended, which was around 300 down on the previous year but close to the Eastercon average for the early 1980s.

My committee member responsibilities were for: science programming; some of the film programme selection; publicity; and (not editing but) publication print. For the latter I turned to two friends, SF aficionados Charles and Harry Nadler of the MaD SF group (not to be confused with the BaD SF group: the Manchester & District SF Group and Bolton & District...). Charles and Harry also printed SF² Concatenation's first edition. The programme book they did for us made Eastercon history, it being the first Eastercon souvenir book to have a full-colour cover. I also secured Harry (who was a former cinema owner) and Graham Connor for film projection duties: yes, we used celluloid back then.

In addition to SF² Concatenation's being an Easter Sunday extra for the four-day event, we were also going to have a firework display courtesy of Los Alamos fandom. Now, we truly had prepared the ground for this and had an area approved for us by the Birmingham Metropole Hotel; we even had air clearance granted us by Birmingham airport up to a thousand feet for the evening. As I remember it -- and my memory may well have become corrupted with age -- one thing we had not reckoned on was that the area the hotel gave us had been deemed by that weekend's hotel reception staff as being just outside what was the hotel's 'quiet' wing and soon there were complaints from airline pilots with an early start as to all the bangs and woooshes. And so, alas, the firework display was curtailed 10 minutes after it commenced. I can't remember whether we had to shift it, or what happened, but there's probably a lesson there somewhere for even the most diligent of event organisers.

As said some 700 attended BECCON '87 which was down around 300 from the previous, and following, year's Eastercons. This was undoubtedly due to a number in Britain's SF community deciding that if they could only afford one big convention that year then they would go for the aforementioned five-day Worldcon that came to Britain that year. However, the 300 shortfall would have undoubtedly been greater were it not for a greater number of local West Midlands attendees due to a public library poster campaign run with the help of the county Council as well as promotional leaflets for the general public.

BECCON '87 ran for four days over the Easter Bank Holiday weekend. There were four programme streams: two main streams of talks and panels; a film stream (held in the hotel's purpose-built cinema [now sadly gone]);and a fan & workshop stream. Programme items included: a debate on whether too much money was spent on space research (no surprises for guessing how that went); space the next 25 years; space programmes that never were; futurology and 'tomorrow's world'; space art; the future of SF awards; Ghost of Honour Speech from H. G. Wells (by Ian Watson); skiffy; SF/fantasy postal stamps; seven quizzes/games; and panels on games, latest books; publishing; comics; alien encounters; Worldcon running among other items that also included a fancy dress parade, disco and a convention 'Christmas' dinner. Films included: Max Headroom (who was huge with the public in the mid-1980s culminating in a two-season TV series, one before and one after BECCON'87), Runaway, Harlequin, First Spaceship on Venus, Time After Time, Cocoon, Master of the World, Asterix and Cleopatra, The Thing, Hour of the Wolf, Dune and Allegro non Troppo among others. Remember this selection was made in 1987 when there were only four TV channels in Britain and no internet hence no access to download films. The film programme back then had to be a mix of old and the new together with a few independent studio productions.

In addition to GoH Keith Roberts, other SF notables attending included: Iain Banks, Ken Bulmer, John Clute, Jack Cohen, Malcolm Edwards, Colin Greenland, Harry Harrison, Rob Holdstock, Terry Pratchett and Bob Shaw.

Anyway, our 30-year reunion went well and with much catching up as some had been in different social, let alone SF, circles for many years. Graham Connor (physicist, SF² Concatenation's co-founding editor, and one of BECCON's film projectionists) led a toast to absent friends and especially Harry Nadler. We then continued to reminisce, muse about current SF affairs and conrunning, and generally put the world to rights (albeit subsequent inspection the following day revealled that little had changed). It was a good gathering.

|

|

Cover of the limited run, pre-publication, promotional edition of Austral.

Cover of the limited run, pre-publication, promotional edition of Austral.

© 2017, Paul McAuley / Gollancz.

Reproduced under fair use in the context of a review. |

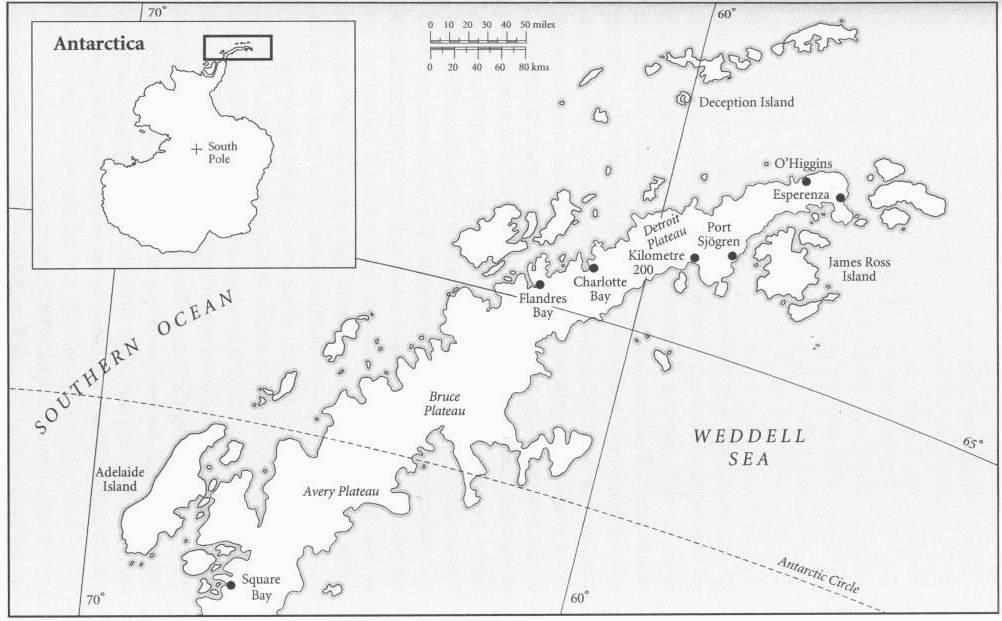

Summer 2017 Coincidence? Science Fiction again parallels science fact! Coincidences do happen, and are not events determined by what Carl Jung called synchronicity. And so it was that Concatenation's arts-science wing had just received Paul McAuley's short article for its series on 20th century scientists that have inspired scientist-turned-SF-authors: Paul was a biologist before becoming a full-time writer. All well and good but, at June's end, his article's submission coincided with our receiving from his publisher (Gollancz) an advance summer, marketing edition of his latest novel's proofs of Austral, due out this October. (This is not the interesting coincidence...)

The coincidence was the advance posting online, and then the publication the following week, of a research paper in the journal Nature on the climate change driven expansion of Antarctic ice-free habitat. (Lee, J. R. et al, 2017, Climate change drives expansion of Antarctic ice-free habitat. Nature, vol. 547, p49-54.) This was a coincidence as the paper presented a merged climate and biogeographic model forecast as to the environment of the Antarctic peninsula. This showed that, even if carbon emissions are curbed, much of the margins of the peninsula would be ice-free by the end of the century, and more under what is effectively the IPCC's Business-as-Usual scenario. It was a coincidence because Paul McAuley's novel, Austral, is set in the 22nd century on an envisioned Antarctic peninsula which has ice-free margins due to global warming and the peninsula is the Earth's newest nation. The story concerns a GM-tweaked woman who accidentally gets caught up in a kidnap attempt and ends up on the run in the peninsula with the victim and both the police and real kidnappers out to get them. The novel comes with a front-piece map of the globally-warmed peninsula, as does the research paper.

|

Above, the likely ice-free area by 2098AD adapted from Jasmine Lee et al.

Above, the likely ice-free area by 2098AD adapted from Jasmine Lee et al.

Blue = current ice-free land. Orange = likely ice-free land by 2098AD under moderate curbing of emissions scenario.

And red = ice free land under Business-as-Usual scenario.

© 2017, Jasmine Lee et al. Reproduced under fair use in the context of a review.

Below, the map in the front-piece of Austral.

© 2017, Paul McAuley / Gollancz. Reproduced under fair use in the context of a review.

What Paul McAuley's Austral novel map does not show are the ice free areas described in the story. These are all confined to the peninsula's margins (coasts), with snow and ice still extant along the peninsula's centre, just as in the Jasmine Lee et al research paper. Indeed, combine the two maps and you'd get the perfect map for the novel.

Some points to note. The science forecast map shows that the northern edge of the peninsula will be more ice-free than the opposite coast which is sheltered from the warming circum-polar current. The Austral novel's map similarly shows more settlements on the northern coast. However, the Austral map does not show any Larsen ice shelves along the peninsula's southern edge. This is quite reasonable as these are likely to have disintegrated by the end of the century depending on where the grounding line lies. (Indeed, a trillion tonne, Delaware-sized berg, bigger than London, at 2,200 square miles (5,800 km²), calved from the Larsen C ice shelf this month: another non-synchronous coindience.) Conversely, the science forecast map shows the extent of the current ice-shelves. This too is reasonable as (most people including some scientists forget) the IPCC specifically (because there are too many unknowns) ignores long term feedbacks and these include ice sheet responses to warming. (If you were unaware of this then look up the four IPCC Assessment reports on the web, download the PDFs and then word search 'long term feedback' and you will find numerous mentions, nearly all being caveats saying that the IPCC scenario forecasts ignore these.) In short, the IPCC's forecasts are conservative underestimates of warming: as said, few realise that!

Relatedly, two weeks later there was another Nature piece, this time an editorial, on Antarctic ice-shelf break up that ends with a comment on the greening of that continent's fringes. The science and science fiction tango has many twists.

And then there's an SFnal point. Some say that today's science fiction is tomorrow's science fact: this, as a point of curiosity has some merit. Some others, including a few who should know better, say that science fiction is not a predictive genre. As a point of pedantry, this too is technically true but that does not mean that some SF can be somewhat predictive: SF is too replete with examples from John Brunner's 1975 novel, The Shockwave Rider (that predicted what is in effect the internet, hacking, computer viruses (he called them phages) and ID theft (in its modern sense)) to George Orwell's 1949 novel 1984 (with its state surveillance some 20 years before the first instance of CCTV in Britain and before its a first instance in Barcelona ironically in a street named after that author). Rather, SF can be predictive, especially hard SF (let alone mundane SF as is Paul McAuley's Austral). SF's relationship with prediction can be considered as an old fashioned blunderbuss pointing in the direction of space-time, hypothetical futures of which only a few come close to what will come to pass. Fire the blunderbuss and much of its shot will miss the small target area that represents the actual future, but there will be a few hits. But even the misses can say something poignant, if not significant, about the human condition as well as our place in the grander scheme of things.

|

'The Pharmageddon Now' House of Lords reception (2002) to address antibiotic resistance that linked in with a similar (Congress-venued) event organised by counterparts in the US. From left: Jonathan Cowie, Prof Nancy Lane (President Institute of Biology ), Andrew Lamb (Chair IoB Biomedical Sciences Committee), Lord Soulsby (House of Lords Science & Technology Select Committee), and sponsor representatives from Pfizer and Bayer.

'The Pharmageddon Now' House of Lords reception (2002) to address antibiotic resistance that linked in with a similar (Congress-venued) event organised by counterparts in the US. From left: Jonathan Cowie, Prof Nancy Lane (President Institute of Biology ), Andrew Lamb (Chair IoB Biomedical Sciences Committee), Lord Soulsby (House of Lords Science & Technology Select Committee), and sponsor representatives from Pfizer and Bayer.

|

Summer 2017 Prof. Lord Soulsby FIBiol passes. It was sad to hear of the demise of Prof. Soulsby. Not only was he a Fellow of the Institute of Biology, one of the bodies of which he served rented the office at the Institute next to mine, so I'd regularly see him and he would often pop his head around the door for a chat. We also occasionally worked together and rather closely when it came to a major initiative (a two-day symposium with a Parliamentary policy launch reception and a House of Lords policy stakeholder dinner) on antibiotic resistance back in 2002. He came to biology through veterinary science and had a broad range of related interests that included parasitology (he was know by some as 'King of the [nematode] worms') through to animal welfare. Regarding antibiotic resistance, his pet avenue he wished to see further consideration was the use of phages (viruses that infect bacteria) as possible antimicrobial agents. This has, until the past couple of years, been an orphan area of bioscience but now the idea of genetically modified phages as antimicrobials is gaining more traction within the research community. Another sadly gone.

|

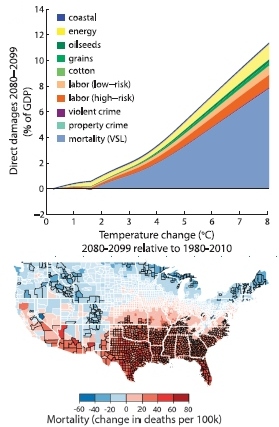

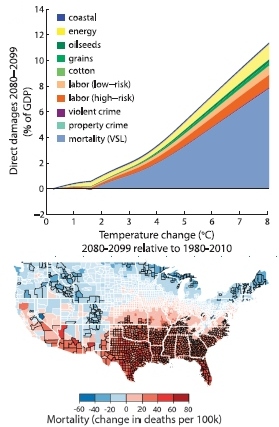

The greatest economic cost to the US of climate change to the end of the 21st century Solomon Hsiang, Robert Kopp and colleagues foresee is that associated with increased mortality.

The greatest economic cost to the US of climate change to the end of the 21st century Solomon Hsiang, Robert Kopp and colleagues foresee is that associated with increased mortality.

© Hsiang et al, 2017, reproduced in the context of a review. |

Summer 2017 The economic cost of climate change to the US has been estimated. Solomon Hsiang, Robert Kopp and colleagues integrated climate change with economic models. Very roughly, costs equating to 1.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) are incurred per +1°C on average. Importantly, risk is distributed unequally across locations, generating a large transfer of value northward and westward that increases current economic inequality. By the late 21st century, the poorest third of US counties are projected to experience damages between 2 - 20% of county income (90% chance) under business-as-usual emissions (IPCC Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5). The greatest economic cost is that associated with increased mortality. Warming reduces mortality in cold northern US counties and elevates it in hot southern counties. Rising mortality in hot locations more than

offsets reductions in cool regions, so annual national mortality rates rise ~5.4 (±0.5) deaths per 100,000 per °C. However, the devil is in the small print. This mortality cost is arguably an over-estimate as the elderly (who generate less wealth -- they actually incur a cost) have less an economic value (albeit they are valued in other ways) than younger economically active individuals. Take this important factor into account and the economic cost from climate-change-induced mortality actually reduces (if not vanishes and becomes positive). The researchers deliberately calculated the economic cost of mortality the way that the US is legally obliged to use for environmental cost-benefit analysis. This paper is therefore interesting both in the way climate change costs and benefits are calculated as well as the pattern of costs and benefits across the nation. Attention to the geographic transfer of economic value is a concern warranting special attention.

The work was published in Hsiang, S., Kopp, R., Jina, A. et al (2017) Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States. Science, vol. 356 (6345), 1362-1369.

|

|

The 12th Bexley Beer Festival.

The 12th Bexley Beer Festival.

And, during the day outside, folk

And, during the day outside, folk

could watch cricket.

|

Spring 2017 Doing press liaison for the 12th Bexley Beer Fest. Though I have been winding down the past few years, I have always had a small part of my work involving press liaison, though these days such activity is only donated for 'good causes'. Indeed, I have been doing press work for the Bexley Beer Festival for a few years even though I am no longer primarily based in Bexley Borough. The Fest is nominally organised by the Bexley borough branch of CAMRA but in reality it is run by unpaid local volunteers, yet does much to promote real ale and support local micro-breweries and pubs. Normally, I just do my bit which I can do from anywhere in the country/world, but this year I was actually in London for other engagements (both unrelated science as well as arts) and so for the first time I could actually attend the Fest itself! (And they kindly furnished me with vouchers for the evening.) Having said that, the basic press liaison I do for them is getting less relevant due to the decline of newspapers (social media is now a necessary complementary half to the work but I don't do that): there used to be six papers in the borough and nearby Dartford and now it is down to just three with coverage in one being essential if the event is to make more than a nominal four-figure sum for the locals. However, this year it did all go well; something you never can guarantee as you cannot physically force the press to cover a story let alone the way you want (and there's always someone who moans that their particular take/nuance was not 'properly' covered), but this year was one of those when the press responded perfectly well (the obligatory winger notwithstanding). The organisers were rather pleased.

There were 85 beers and ciders on sale, not including an additional 8 casks supplied by traders Bexley Brewery. Over 1,600 people attended; a record and 300 more than last year. They consumed a total of 7,000 pints of ale and 1,000 pints of cider: a total of just over 4,500 litres of beer and cider. They included those from local breweries including Bexley Brewery, Tankleys, Brew Buddies, Beerblefish, Westerham and Kent Brewery with Caveman Brewery (from Swanscombe, geddit?) on sale in the Dartfordians Club House next to the Fest's marquee. The most popular cider was from Ampleforth Abbey (Yorkshire).

|

|

|

Spring 2017 Spring jollies. Though I still go to symposia related social / networking gatherings, I have cut right down on science policy junkets as I slip into what will eventually be retirement (though life is as full as ever). However because of my science-arts activities I do get regular invites to other jollies, including book launches, promotional gatherings and the like, and these are nice to do from time to time when I am down south near town. Normally I don't mention these that much on this site, but I now give two shout-outs in thanks for a couple of spring's invitations as I am not sure I deserved them. One was for the Gollancz bloggers (and webmasters) evening (Gollancz are the people who also do SF Gateway), and the other for the Sci-Fi London pre-opening stakeholder reception.

|

|

|

With regards to the former, as SF² Concatenation's News are Reviews Editor, I'd have provided coverage anyway, though as always it was nice to meet the Gollancz folk face-to-face for a change. (STOP PRESS: See above some science and SF news above regarding a new Gollancz novel.) As for the latter, I haven't done anything for Sci-Fi London for a few years now (though may will again sometime) but it was good to meet film folk, directors, producers as well as some fellows from Britain's SF community. Anyway, the folk at both were very kind. If you are an SF aficionado with a literary bent then the Gollancz's current seasonal catalogue is always worth checking out: SF² Concatenation cites their new titles on its news pages' forthcoming books lists. And if you are of an SF cinematic bent then it really is worth checking Sci-Fi London's website out early each April to see what they're showing.

|

|

|

Spring 2017 The March for Science went well and saw a good number of doctorates mobilised, including one proverbial good 'Doctor'... With the rise of 'fake news' and more-than-usual dysfunctional political performance (EU Greek finance, Brexit, US election, Turkey's response to the failed coup etc., etc.), not only are nations' investment in science threatened, there is anti-science abounding ranging from climate change denial to censoring science education (the latest being Turkey removing evolution from its schools' curricula as it is apparently 'controversial' and 'too complicated'). And so scientists worldwide decided to remind the public (and politicians) that we exist as people and lobby the evidence-based cause.

As one of those scientists into SF (or was it SF turning me on to science?) it was a delight to see Doctor Who (Peter Capaldi) at the London rally. The event was held on Earth Day. (Summary coverage from the BBC here.)

|

|

|

|

Update: August 2017. An adendum for the above for completeness' sake. The London March was one of some 600 city gatherings for science, its research and evidence-based policy. Included in the mix were just two Indian cities. Two is not many for such a populous nation let alone a technologically advanced, space-going one. Apparently, this was not because of any lack of interest in science in India but because the perception was that the 22nd April's March for Science was more to do with US President Donald Trump's anti-science policy-making and funding. India's problems are different and, despite successive governments stating that they aim to raise research investment to 2% GDP, India's investment has remained at around 0.9%. And so on 9th August some 40 Indian cities saw gatherings for science. There is also concern in India for the government's support for unscientific ideas such as the health benefits of cow products such as urine: Hindus regard the cow as sacred. Alas, I did not make any of the Indian events, but was there in spirit.

|

|

Jonathan with Philip O'Donoghue on his 70th birthday, 1998.

Jonathan with Philip O'Donoghue on his 70th birthday, 1998.

No. 20 Queensberry Place of the former Institute of Biology that was at both 20 - 22 Queensberry Place up to 2004 when the properties were sold in a good deal for someone. No. 20 itself now contains a number of flats but had been a 7-bedroom house on sale in 2010 for a mere £12 million.

No. 20 Queensberry Place of the former Institute of Biology that was at both 20 - 22 Queensberry Place up to 2004 when the properties were sold in a good deal for someone. No. 20 itself now contains a number of flats but had been a 7-bedroom house on sale in 2010 for a mere £12 million.

|

New Year 2017 Philip O' Donoghue MSc CBiol FIBiol RIP. News arrives that before Christmas Philip had passed following a prolonged period of illness. Philip had spent some time as a technician at NIRD (the National Institute for Research into Dairying) where he became subsequent life-long friend with Prof. Marie Coates.

NIRD was an AFRC (that would later be subsumed into what became the BBSRC within the UK Science Base) Research Institute that sadly closed in the 1980s (merging elsewhere with the Institute of Food Research due to the political perception that farming had too much being spent on it and so did not need much research investment (and then in the 1990s we had: the national salmonella in eggs issue, BSE/CJD, GM crops, etc. issues, but all that is another story).

Coincidentally, I happened to work at NIRD as a (very much junior) technician for 15 months in the 1970s as my gap year between school and college, in Marie Coates' Nutrition Department, but not at the same time as Philip (who in any case had been in a different department).

I met Philip when I joined the Institute of Biology as Philip was then its General Secretary (what today would be called Chief Executive) and so he was my line manager. Philip retired from the Institute in 1988 but I did still occasionally see him, including once with the then also retired Marie Coates at one of my science policy meetings at the Institute along with representatives of its 70+ Affiliated Societies: it was the only time I saw the two of them together and so it was a bit of an occasion. At work he was known for being a great lunch time raconteur and, like the Higgs boson, always had a small crowd around him on London's evening science reception circuit. Philip, I raise a glass of malt to you.

[Past news 2015/16]

[Bioscience interactions | Climate change interactions | Science & Fiction interactions | What is Concatenation all about? | Home ]

|

|